Today’s newsletter is rather long and might be truncated in an email, you can click on "View entire message" to view the entire post in your email app.

I fell in love with the vast landscapes of the Great Plains the moment I set foot on them for the first time. I have returned many times with my camera, trying to capture both the harshness and beauty of the land with its endless skies and my own feelings towards it.

The Great Plains have been a great source of inspiration for my creative projects in the past, from photography to collages and zines. I have delved into the history, learning about the lives of early settlers, the hardships they faced, and the different reasons many abandoned their homes in search of a better life elsewhere.

When I first learned about photographer Lora Webb Nichols and the book Encampment, Wyoming, I was immediately intrigued. Her story had been long forgotten, and the discovery of her photographic collection, tucked away for decades in a small, local Wyoming museum, is largely thanks to Jean Nicole Hill, a Professor of Art at Humboldt State University.

In 2012, during a brief visit to the Grand Encampment Museum in Encampment, WY, Hill stumbled upon a small exhibition featuring photographs by a local photographer. A small note alongside the display revealed that the museum housed Nichols’ archive – an astonishing collection of 24,000 negatives, all made between 1899 and 1962.

Hill, a photographer herself, was determined to find out more about this female photographer. She contacted the museum staff to arrange another visit to take a closer look at the archive.

This is when she met another important figure in this wonderful discovery: Nancy Anderson. A teacher, historian, and local of Encampment, WY, Anderson was also a friend of the Nichols family.

She had bought Nichols’s house after her passing in 1962, many of her belongings still in the house:

“The remnants of Lora’s library, her old guitars, the upright piano in the parlor, the issues of The Grand Encampment Herald under her bed, and, above all, her negative files, her diaries, and her memoir, I Remember, were all once enclosed in a massive autobiographical envelope, Heap o’ Livin’, as she called the 1902 relic Encampment’s brief day of shining copper glory.”1

Recognizing the historical importance of Nichols’ work, Anderson – who had been named as the curator and caretaker of the archive by the Nichols family – worked closely in collaboration with the Grand Encampment Museum to ensure that the negatives were preserved under the right conditions.

In the 1990s, Anderson, her husband, and a few volunteers undertook the enormous task of scanning all 24.000 negatives and saving them onto DVD-RAM discs.2 Yes, you’ve heard that right. DVD-RAM – It was the 1990s, after all.

In 2013, Hill started – with the support and encouragement of the Grand Encampment Museum and Nancy Anderson – volunteering her time and expertise to make the entire archive accessible to the broader public.

Thankfully, the Nichols family eventually donated the negatives to the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming, signing over the image rights to the public domain to maximise use and accessibility in the future.3

But now, let’s take a look at Laura Webb Nichols, her life, and her amazing photographic legacy, which offers us a unique glimpse into the history and people of Encampment, Wyoming.

A brief history

Lora Webb Nichols was born in 1883. Her family, who came to Encampment, WY, in 1879, were among the earliest homesteaders of the town - which wasn’t more than a handful of wooden buildings and a huddle of tents.

In 1899, she received her first camera as a gift for her 16th birthday. It was given to her by a local miner – Bert Oldman – who was courting her at the time and later became her husband. Her father gifted her a developing kit, allowing her to process her photographs.

From that moment, photography became an integral part of her daily life. She documented everything and everyone in and around her hometown.

Because only a few people in that area had her skills and equipment, she was soon hired by local mining companies to document the infrastructure and architecture, as well as the rise of the copper boom, when she was in her early 20s. She also started to work as a portrait photographer, developing and printing from a darkroom she had set up in the home she shared with her husband and their children.

Nichols established the Rocky Mountain Studio, a photography and photofinishing service, to help support her family. Her commercial studio was a focal point of the town throughout the 1920s and 1930s. As an official Kodak photofinishing service, she developed film dropped off by people at the local drugstore. Occasionally, she even paid her customers for the right to keep their negatives, adding them to her growing collection.4

In 1935, Nichols left Encampment and moved to Stockton, California, parting ways with her husband and children to pursue a new chapter in her life. Though she continued taking photographs, she no longer relied on photography as her primary source of income.

Nichols eventually returned to Wyoming in 1956, where she lived until her passing in 1962 at age 79.

Her photographic legacy

Over six decades, Nichols photographed the life around her and made over 20.000 photos during that time. She photographed friends and family, customers and strangers, interiors and landscapes, and documented the everyday activities in her community.

Nichols’s vast photographic collection is both unique and invaluable in at least two ways: Not only does it offer a rare glimpse into the history and the people of a small community on the Great Plains, but it also presents this world through the eyes of a working-class woman - an uncommon perspective for the time:

“Lora does not fit the usual narrative of female photographers from this era, which commonly places cameras in the hand of wealthy women that pursued the medium as a pastime.”5

What I love about Nichols’ photographs is their intimacy and honesty. While her perspective is often straightforward, her portraits feel natural and unstaged. One can feel the connection and trust between Nichols and the people she photographed.

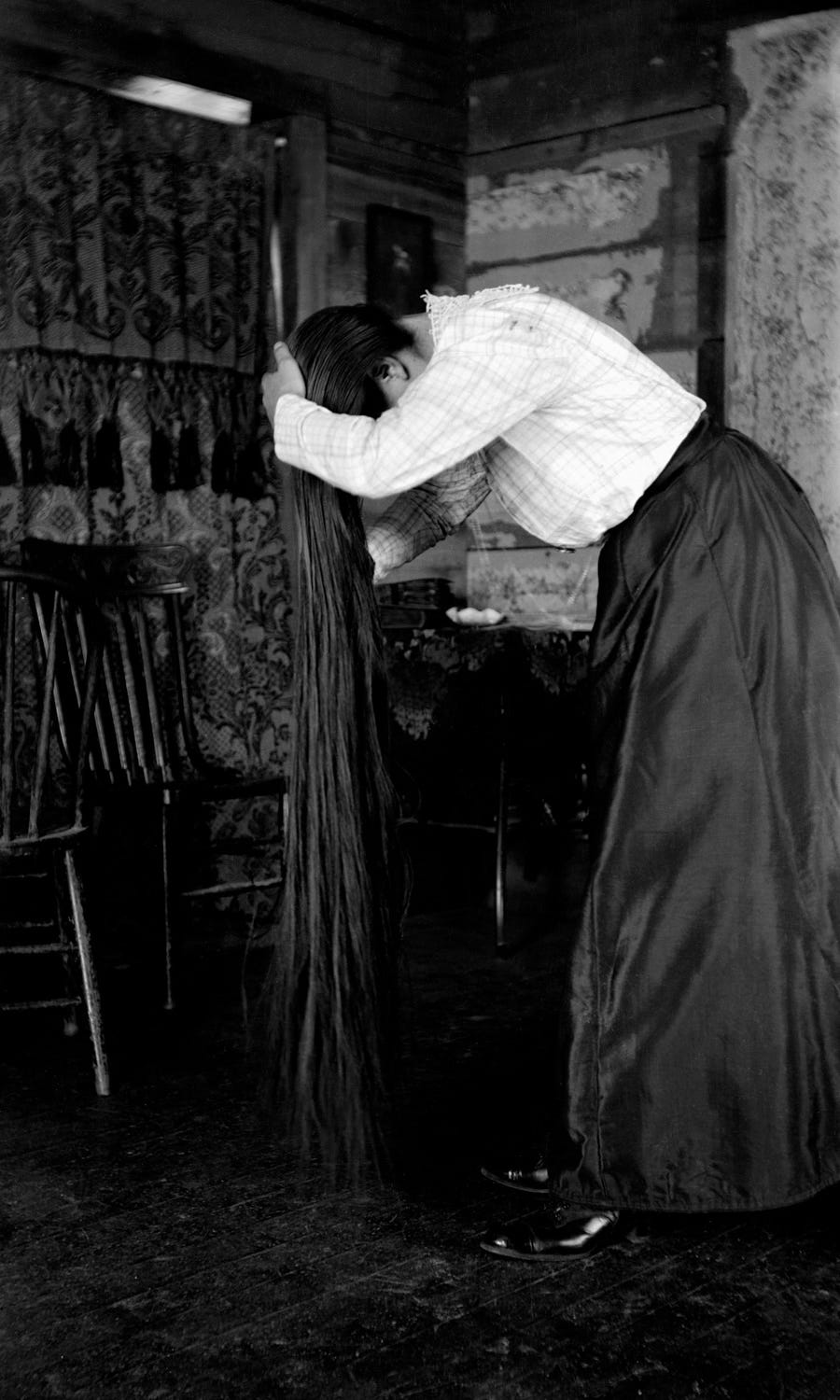

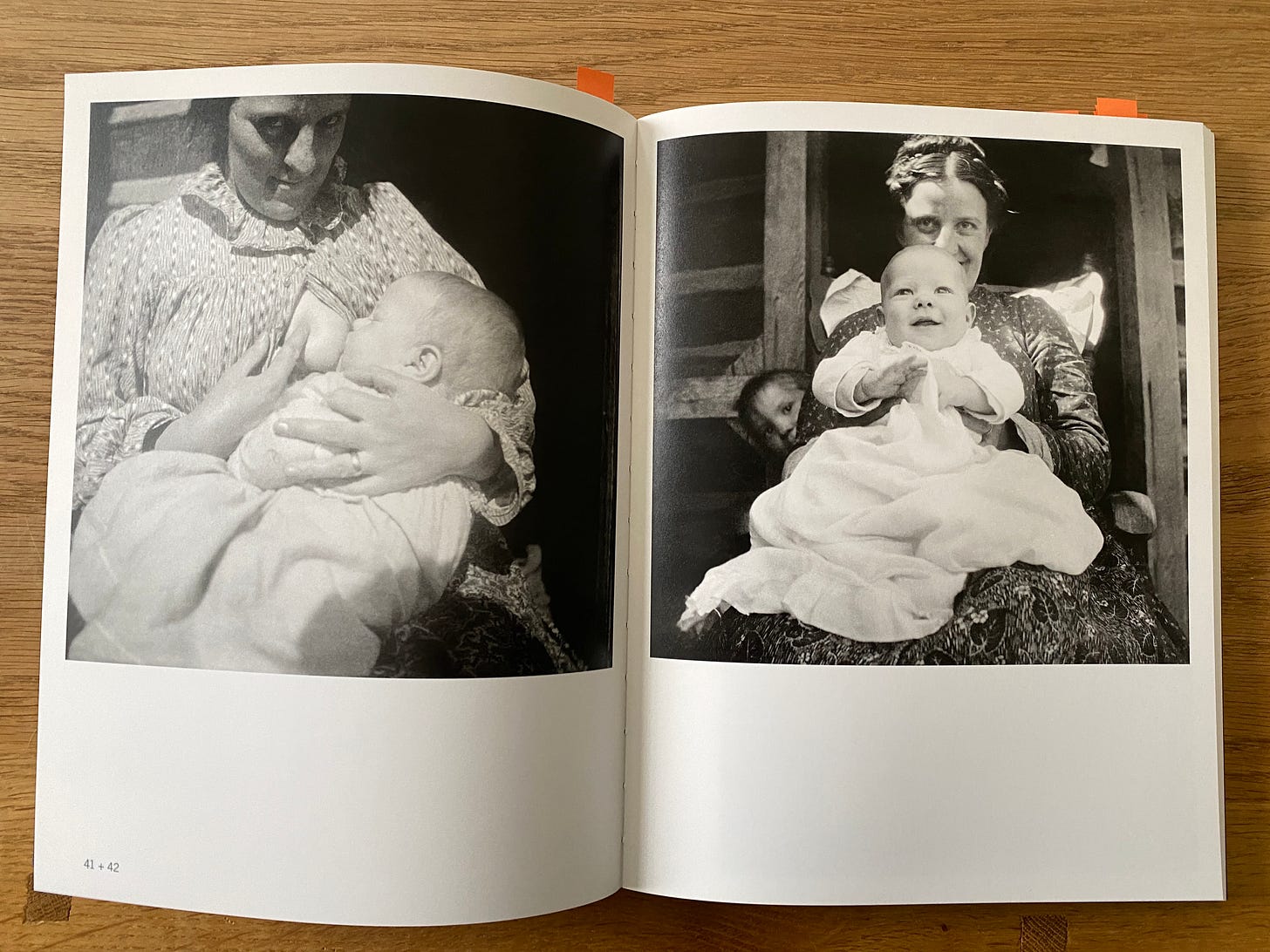

There is so much more to say about her, but for now, I’ll let her photography speak for itself. These, in particular, speak out to me because they feel so intimate, and in a way, female to me:

And here are a few excerpts from the book “Encampment, Wyoming” which I find remarkably well-matched:

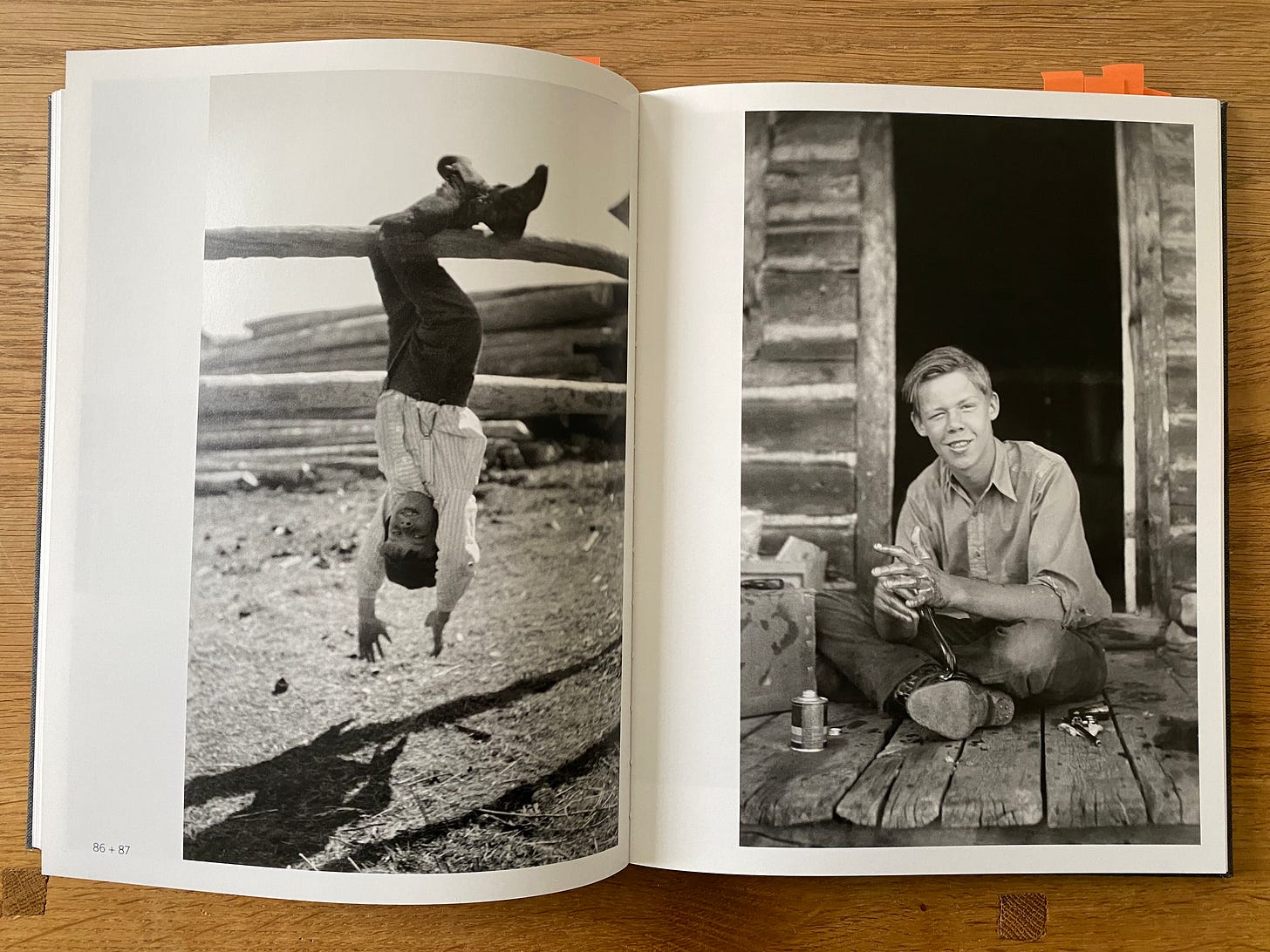

And a few double spreads I find just exceptional:

And one last photo because it always makes me smile looking at it:

Another interesting fact is that Nichols kept a daily diary for more than sixty years:

“Spanning her life from age thirteen to seventy-nine, they portray the richness and complexity of Lora’s experience of the world, providing an expansive narrative of her time and place. They capture the humour, fears, and frustrations and the mundane day-to-day comings and goings of friends and family throughout her life. Regular accounts of whom she photographed or who photographed her intermingle with description of business ventures, family activities, social events, and daily chores, revealing how photography was nearly a daily practice for Lora.”6

If you want to learn more about Lora Webb Nichols:

Jean Nicole Hill maintains a wonderful website to showcase the amazing work of Lora Webb Nichols. I highly recommend visiting it: www.lorawebbnichols.org

I highly recommend the book. It is simply beautiful: the design, the paper, the sequencing, and of course, the photographs. It looks like it is still available on the website.

I watched a few videos on YouTube on her, but I liked this one the best:

I began my mission to write about female photographers after standing in front of my bookshelf one day, realising how much my photobook collection was dominated by male photographers.

I am a self-taught photographer with no formal art history or photography education. I do not have the expertise or knowledge to give you a deep analysis of the work, nor do I see myself as intellectually equipped enough to place the work within a historical context.

My aim is simply to share the work of women photographers who inspire my creative journey – along with their stories and unique perspectives on the world they live(d) in.

If you are interested in reading more, you can find all past editions here.

That’s all from me this week.

Thank you so much for being here and for taking the time to read this week’s newsletter. It means a lot to me! Feel free to leave a comment – I always love to hear your thoughts.

X,

Susanne

WAYS TO SUPPORT MY MORNING MUSE

If you enjoy reading my weekly newsletter and would like to support my work, here are a few ways to help me keep going:

🪶 Like, share, or comment - it’s free and greatly appreciated

🪶 Upgrade to a paid subscription (only €5 per month)

🪶 Purchase one of my zines

🪶 Treat me to a cup of tea

Thank you so much!

Nancy Anderson in “Encampment Wyoming - Selections from the Lora Webb Nichols Archive, 1899-1948”- Unfortunately, there are no numbers on the pages..

Nicole Jean Hill in “Encampment Wyoming - Selections from the Lora Webb Nichols Archive, 1899-1948” - Unfortunately, there are no numbers on the pages..

see above. Unfortunately, there are no numbers on the pages.

Jean Nicole Hill estimates that 20 percent of Nichols's archive are negatives from her customers.

Nicole Jean Hill in “Encampment Wyoming - Selections from the Lora Webb Nichols Archive, 1899-1948” - Unfortunately, there are no numbers on the pages..

see above.

Such a great story! Very interesting to read and understand that so many great photographers still waiting to explore them by finding archives of negatives under the bed or on there shelves after they passed away. But a little sad to think in this way also.

Great post, Susanne! I remember hearing Alec Soth discuss Lora's work, though I can't recall where. The photo of Lizzie with the cat truly amazed me, especially when I noticed the crutch! I had forgotten about it until now, but I'm enchanted by it once again. Thank you for sharing!