When we think of photography, we usually think of some sort of device like a camera or -nowadays- a mobile phone, which we point at something, push a button, and shortly after, an image appears on the screen. But when we look back at the beginnings of photography, we learn that the very first photographs were actually created without a camera. All that was needed - and technically still is - was light and a surface that would react to it. And this is what the word photography means: the Greek word phōtos, means light, and graphé can be translated as drawing lines — so photography is essentially drawing with light.

In 1727 the German professor of anatomy Johann Heinrich Schulze proved that the darkening of silver salts, a phenomenon known since the 16th century and possibly earlier, was caused by light and not heat. He demonstrated the fact by using sunlight to record words on the salts, but he made no attempt to preserve the images permanently. 1

A hundred years later, William Henry Fox Talbot solved the problem of making the images permanent. He would create camera-less images by placing objects like pieces of lace on sensitized paper. After exposing it to light, he would fix it using sodium hyposulphate to make the image permanent. A technique still used today.

Because this technique has its limitations, only a few people used this technique once the camera had been invented. But there are still artists until this very day who use this or similar techniques to create unique photographs without a camera.

Last year I bought a book called “Shadow Catchers - Camera-less Photography” by Martin Barnes, which presents five artists and their approaches to camera-less photography. All of them have very unique ways to create images, but one of them fascinated me the most, because I have never seen anything like it before: the chemigrams by Pierre Cordier. But before I try to explain his work, here is a little video:

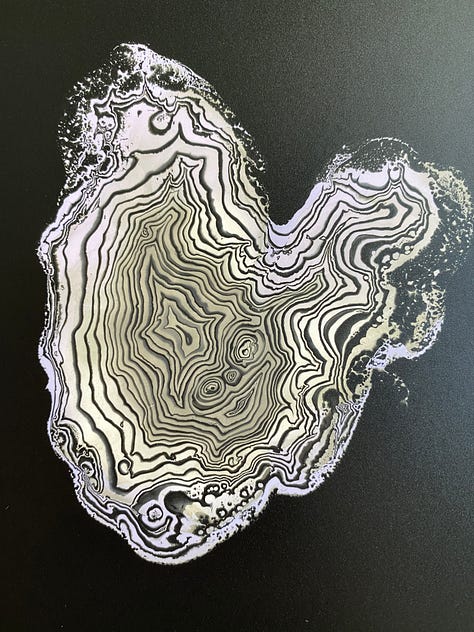

I was so fascinated and baffled by his work, and still am. It would never have occurred to me to use nail polish or sugarbeet syrup on photo paper, but after I did some research, I found that you could use all kinds of materials on photographic paper to create an image. So, I searched my pantry for “ingredients” to create my own chemigrams. I used liquids like honey, syrup, oil and butter, applied them to the light-sensitive photo paper, exposed it to light and dipped it into the developer or fixer. The liquid slowly resolved, and lines and marks emerged, creating these fascinating patterns.

It took some time to figure out how to achieve specific results, and I wrote down everything in my notebook to remember everything: the liquids I used, the exposure and developing times and things I observed during the creation. I felt more like an alchemist than a photographer or painter. It was a fun experiment. And a very messy one too. The containers with the fixer and developer quickly became a sticky mess full of all the liquids which slowly came off the photo paper.

Here are my favorite chemigrams from this experiment:

This is all from me of today. I hope you enjoyed this weeks edition of my newsletter.

Please feel free to leave a comment. I would love to hear from you.

And as always: Thank you for being here.

Susanne

PS: And if you haven’t yet, please consider to subscribe to my newsletter. You are also welcome to share it with others.

https://www.britannica.com/technology/photography

These are fascinating! I’m beginning to delve down the rabbit hole of alternative processes myself. My end goal is to find a digital hybrid orotone methodology if I can. Although currently planning a summer of Cyanotype printing with a view to eventually learning to make prints on glass.