The last couple of weeks I have been down the rabbit hole of the history of photography. More precisely, I was reading more about sequencing, because I knew there must be more about it than what I wrote in December of last year. But somewhere I must have taken a wrong turn because all of a sudden I found myself reading about the first abstract photographs ever made. I was so fascinated by them, that I decided to abandon my initial plan (at least for now) to learn more about the beginnings of abstract photography.

It was in 1916 - at a time when photography still struggled to be fully accepted as a genuine Fine Art - when the American photographer Alvin Langdon Coburn (1882-1966) created the first non-representative photographs.

Coburn was a well-established landscape and portrait photographer in New York and London. He had studied under several well-known photographers of that time such as Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen and Gertrude Käsebier. Coburn’s work was exhibited in several prestigious galleries in London and New York.1

Why, I ask you earnestly, need we go on making commonplace little exposures that may be sorted into groups of landscape, portraits and figure studies? … I do not think we have begun to even realise the possibilities of the camera.

- Alvin Langdon Coburn

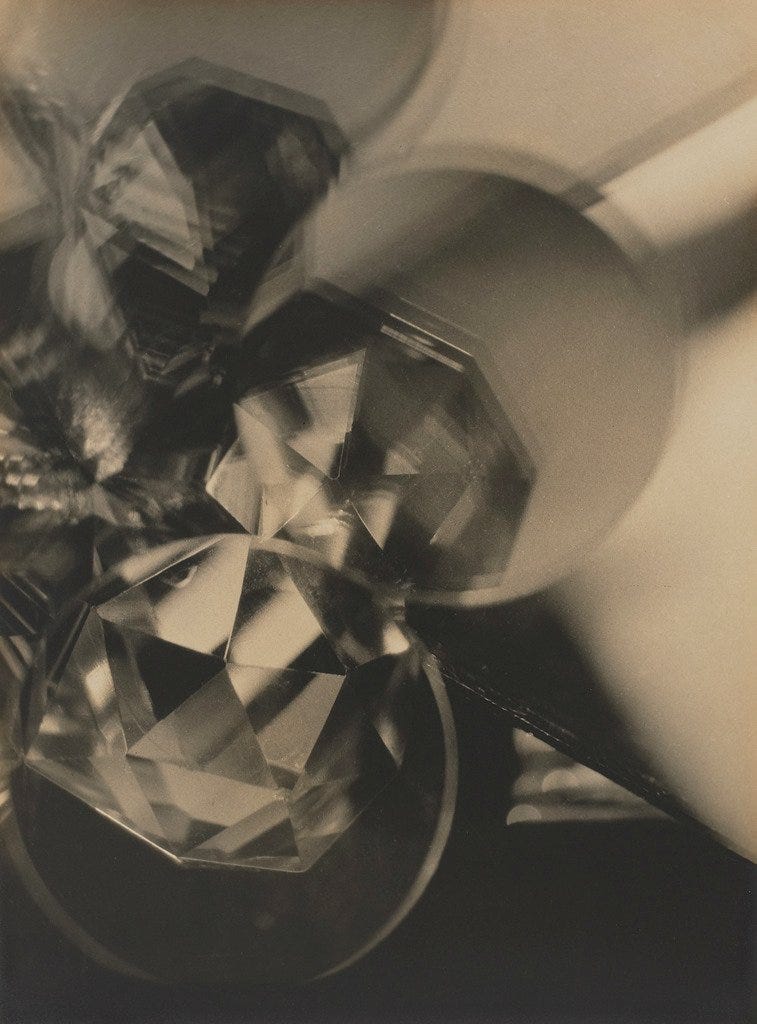

When in 1916 his friend, the poet Ezra Pound, introduced him to the 'Vorticists', a small English art movement influenced by Cubism, Coburn was deeply inspired by the visual aesthetics which favoured geometric forms of abstract nature. He tried to incorporate this style into his photography.2

To do so, he created a tool, that is similar to a kaleidoscope (which had been invented a hundred years earlier): three pieces of mirror joined together in a triangular shape, which when fitted over the lens of the camera would reflect, distort and fracture the object in front of it.

The images Coburn produced using this attachment were so different from the traditional representational photography at that time. Abstract forms, geometric shapes and dynamic lines dominate the image and through the fragmentation, reality appears blurred and distorted. And yet, Coburn’s images convey a sense of movement and energy that fascinates even after over a hundred years of their creation.

Ezra Pound was the one who gave Coburn’s self-made device the name Vortoscope and called the created photographs Vortographs. Coburn made a total of 18 Vortographs which when exhibited for the first time created quite an uproar:

“When exhibited at the London Camera Club in 1917, the eighteen images elicited general outrage. One reviewer suggested they were the result of "poseuritis." Even Coburn's friend and fellow photographer Frederick Evans called for the return of "sane art" and implied that these images were probably evidence of a misguided youth.”3

Coburn created this little series of artworks in the short period of just one month in 1916, and yet they are considered to mark the beginning of a new era in photography. You can find more of the Vortographs in the Eastman Collection.

After studying Coburn’s vortographs for a while, I am convinced Coburn did not create all of them using his Vortoscope. Some look more like multi-exposures, while others look like he just used a mirror to reflect, copy and distort the object. But regardless of how they were made they are all prove

“that photography was not incompatible with abstraction and only capable of rendering a helplessly accurate and literal copy of the real world.”4

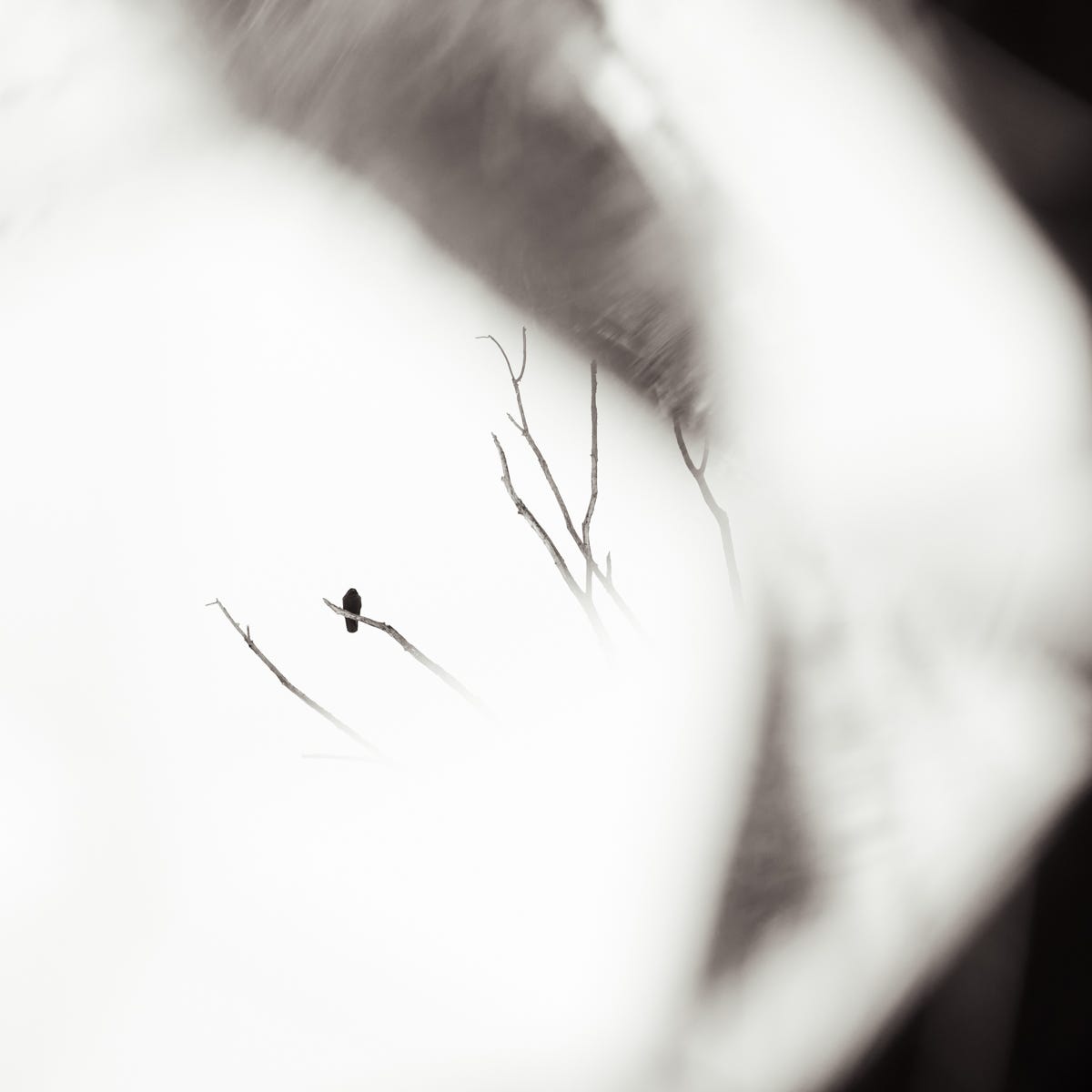

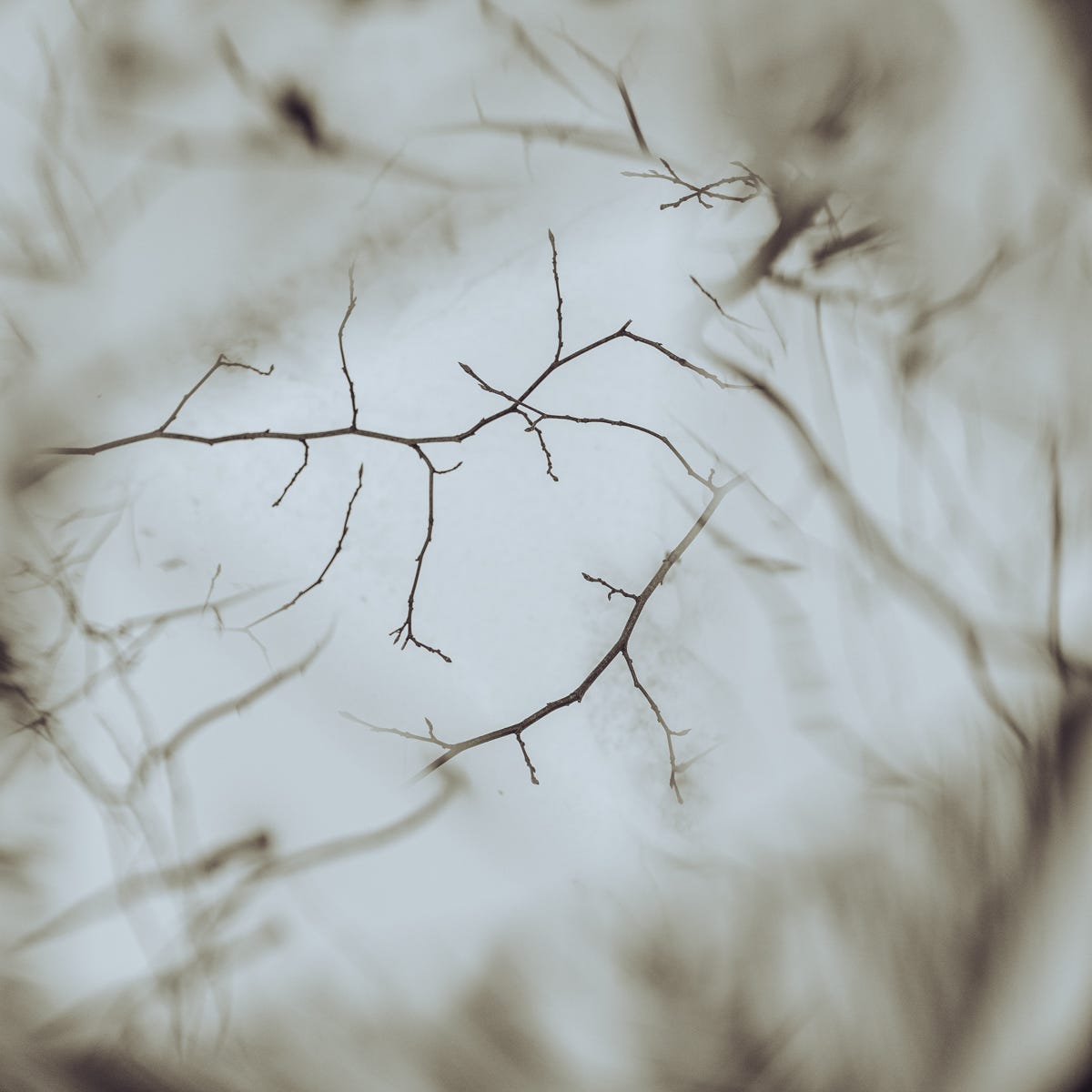

I was so curious about the process and how he managed to create these fragmentations in his images, I decided to experiment with it myself. I created my own vortoscope and attached it to my compact camera. Here are a few of my own “Vorthographs”:

Depending on the subject and the background, the way the vortoscope is attached or held in front of the camera, the camera and lens you use, the results can all be very different. But all the effects are very interesting and unique.

Overall, I enjoyed this little experiment as it provided useful insight into how Coburn created his vortographs and how much work was involved in the process of their making.5

Looking at Coburn’s vortographs with ‘modern’ eyes his creations might look like nothing really special. All kinds of tools and weird lenses are available nowadays to create unique-looking photographs. Software like Photoshop gives us countless digital tools to manipulate an image in myriad ways. Not to mention AI which allows us to create images without using a camera at all. But if we try to look at these vortographs with the eyes of people from hundred years ago, these creations are quite unusual and interesting. No matter if you like them or not, they catch your eye and make you wonder. At least that is what they did for me. And I hope you enjoyed learning about them too (if you didn't#t know about them already).

That’s it from me today.

Thank you for being here and for reading this week’s newsletter. It means a lot to me!

X,

Susanne

If you enjoyed this weeks topic, I would love to hear from you. Please share your thoughts in the comments with me.

If you enjoy My Morning Muse, you can support me by subscribing to my newsletter, liking the post, and sharing it with friends. It would mean the world to me! ❤️

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alvin_Langdon_Coburn

https://www.moma.org/interactives/objectphoto/objects/83725.html

https://www.gallery.ca/collection/artwork/vortograph

https://boshamgallery.com/blog/28-what-is-a-vortograph-the-world-s-first-truly-abstract-photographs-were-made/

Of course Coburn had a lot more work to do developing his in the dark and not digitally like I did.

Wow! You hit a grand slam with these. You gotta keep on this trail, the images are compelling. I was just thinking about figure/ground images vs abstract recently. If you haven't, look up Frederick Sommer's abstractions and cut outs. Man Ray, Maholy-Nagy, etc.

Thanks for these stories and sharing of important photography history.