Imogen Cunningham

A female pioneer of photography

Two weeks ago, I announced in my newsletter that I would like to focus a little more on female photographers here. In the past year, I have written about photographers like John Gossage, Robert Adams and Edward Weston because I am inspired by their work. But exclusively, all of them were men. I wanted to change that. The positive response to my idea was immense and many of my readers agreed with me on the fact that female photographers are underrepresented. I received one comment that resonated a lot with me:

“My point is only that it is what women have brought to photographic images in revealing their personal perspective on our world that makes women photographers worth exploring as “women photographers.” And I think there is tremendous value in seeing how women have viewed the world differently from their male counterparts, although it is complementarity that matters rather than difference because complementarity extends our sense of the world.”1

I couldn’t have said it any better. We all see the world with different eyes and experience it differently. Not because we all are individuals, but because our gender, race and ethnicity inform our way of living and seeing and the way we express ourselves as artists. Shining a spotlight on female photographers isn’t just about underrepresentation, but about what these women bring to the table.

When I shared the little story about Sarah Anne Bright - the creator of one of the earliest photos that survived, many of you enjoyed the story. But I also received comments, that we should rather talk about all the amazing female artists who are still alive. And I agree. But I also find it important to take a look back at the amazing women who have paved the way for us. And that is what I want to do today.

The woman in my spotlight today does not only inspire me photographically, but also on a human level.

Her name is Imogen Cunningham.

I will not write down her whole biography here although it is really interesting and impressive. But to keep this newsletter short, I will just share my personal highlights about her as a woman and a photographer.

A female Pioneer of Photography

Imogen Cunningham was born on April 12th, 1883 in Portland, Oregon. The idea of becoming a photographer had been on her mind since childhood. Her photographic journey began when she -at the age of 22 - bought her first 4x5 camera and a bunch of glass plates. Although her father wasn’t crazy about his daughter’s idea of wanting to be a photographer, he built her a shed in the garden to use as a darkroom.

She studied chemistry at the University of Washington and in the following two years (1907-1909) she took on a job in the studio of photographer Edward S. Curtis where she learned the techniques of the platinum printing process and all about the business of having a portrait studio. In the fall of 1909, she received a grant which allowed her to study photochemistry at the Technische Hochschule in Dresden, Germany.

Once back in Seattle, she started - with the little money she had left - her own photography business. By then she was 27 years old.2

An early feminist

“It is not so much a matter of suitability to sex as to individuality […]. Women are not trying to outdo the men entering the professions. They are simply trying to do something for themselves. […] Photography is […] a craft or trade to which both sexes have equal rights […].3

These words are part of an essay Cunningham wrote in 1913 when she was thirty years old. The essay was titled “Photography as a Profession for Women” and was meant to encourage women to consider photography as a professional career and it offered helpful insights and advice. Quite revolutionary and modern for that time.

If I were to find someone in my family born around that time, it would be my great-grandmother. I don’t remember her well enough, because she died when I was ten. But when I think of my grandmother and mother for that matter, they were far from being feminist or independent. They both grew up in a culture in which women were destined to care only about what we call in German “Die drei K’s: Kirche, Kinder, Küche” (The three K’s: Church, Kitchen, Children).

And reading about Cunningham’s own mother shows she wasn’t very different from that. She described her mother as a quiet, gentle woman who never spoke up and considered her a typical victim of the times. Her mother’s center of the world revolved around cooking, sewing, milking cows, feeding the chickens and raising the children.4

Considering the time Cunningham had been growing up, I find her independence and determination very impressive and inspiring.

Family & Work

Her personal life began to change when she met the fellow artist Roy Partridge whom she married in 1915. In the same year, she gave birth to their first son and two years later they had twin sons. Even though she devoted herself to motherhood in the coming three years, she never stopped photographing. She didn’t take on any commercial work, but she photographed her children and the flowers in her garden.

Her botanical studies of magnolia flowers, aloe plants and other floral still lives later gained much attention in the photographic world and remain some of her most famous photographs.

In 1934 Cunningham’s marriage to Roi Partridge ended in divorce. Their three teenage boys remained in the family home with their mother until they finished high school. Cunningham never remarried, and although she received the house as part of her settlement, the divorce was the beginning of three decades of financial difficulties. Without the second income of her husband, Cunningham had to work even more to stay afloat.5

Important influences and contacts

During her lifetime Cunningham built up an impressive client base. She made connections to the most important people in the world of photography and many of these contacts turned into lifelong friendships. Especially in the Bay Area of San Francisco where her family had moved to in 1917. It didn’t take long for Cunningham to befriend other photographers and artists such as Dorothea Lange, Edward Weston and Margrete Mather who had been living and working there.

These new acquaintances and the new environment she found herself in, had a big influence on her creative vision and her development as a photographer. Cunningham’s style soon moved away from the pictorialist - which was charaterized by soft focus and a dreamy quality - towards a more defined, detailed and clear presentation of the subject.

This radical change of style was noticeable in her photographs of flowers but also became visible in her portraits.

Editorial work

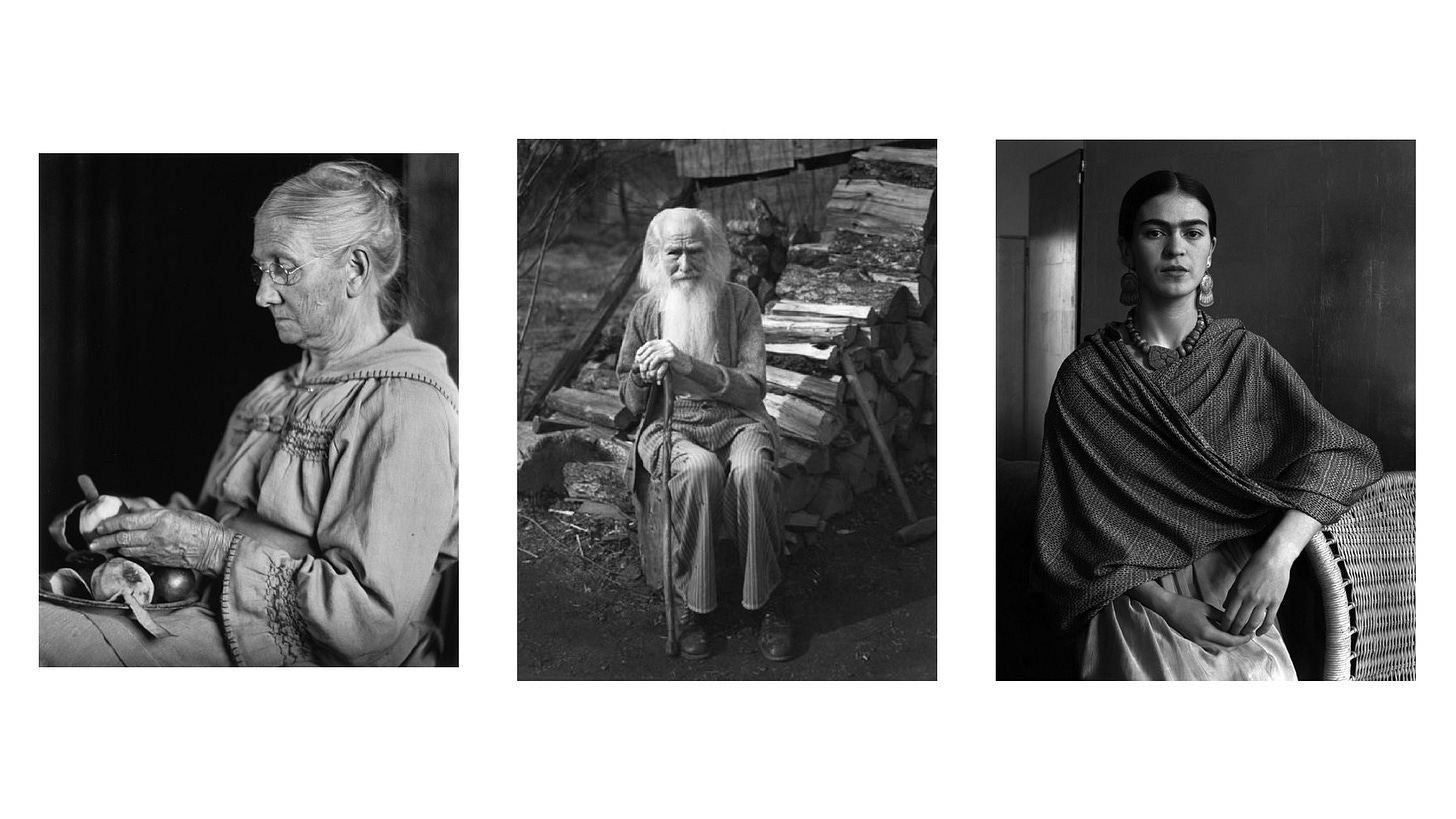

In 1931 two of Cunningham’s images were published in the magazine Vanity Fair, which was a breakthrough for her. In the following years, she was commissioned to work for several other magazines such as LIFE, U.S. Camera, House and Garden and Fortune.6 During her long career, she had many celebrities from Hollywood, politicians and artists in front of her camera: from Cary Grant to Spencer Tracy, to Herbert Hoover and Frida Kahlo.

Known for her striking portraits, she really made a name for herself.

Photographic diversity

Cunningham is well known for her portraits and photographs of botanical still-lives. But having worked as a photographer for seven decades and having witnessed numerous changes in the medium during her photographic career, she experimented not only with different styles but also with different subjects.

Having maintained a considerable interest in German culture Cunningham drew a lot of inspiration from European photographers like Albert Renger-Patzsch and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy who both were practicing the “New Objectivity” (Die Neue Sachlichkeit) - a style which sought to reveal the material properties and geometric value of the industrial landscape with clarity.7

Cunningham started to work on a series of industrial subjects in the 1920s herself, which she -thanks to Edward Weston- was able to exhibit in Stuttgart, Germany in 1929.

In 1932, Vanity Fair commissioned her to go to New York to photograph Alfred Stieglitz and his gallery in Manhattan. During her stay, she would go on walks to photograph the streets and people of New York. She later continued this in her city, San Francisco.

In addition to her work as a portrait photographer, her personal projects and the work she was commissioned to do for magazines, she started to teach photography at the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco. She worked alongside Ansel Adams, Dorothea Lange, Minor White and Edward Weston, who were teaching photography there as well.

In 1960 - Cunningham was 76 then - she took a trip to Europe to visit her colleagues Paul Strand and August Sander and to photograph the streets of Munich, Berlin, London and Paris.

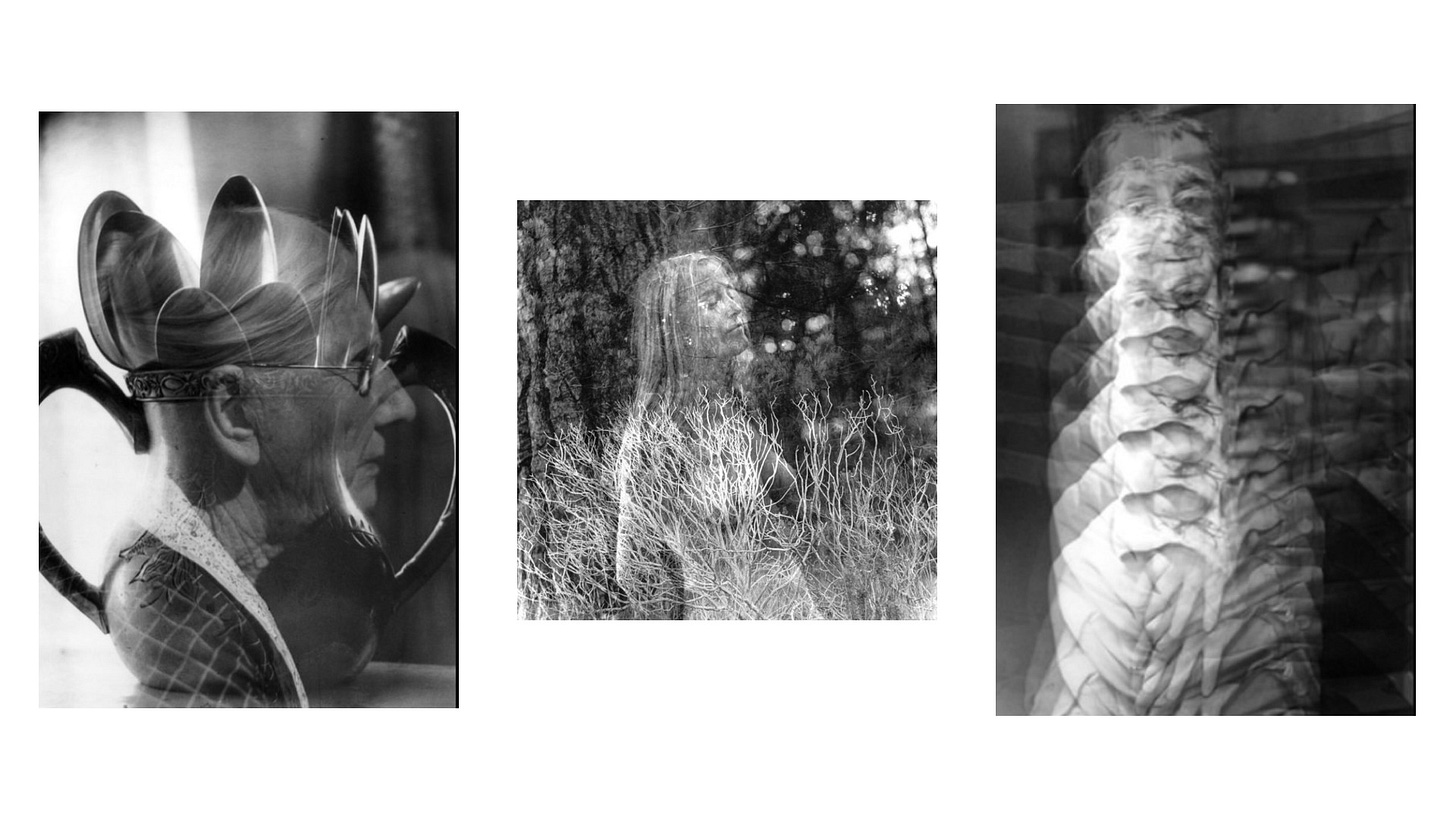

On a second trip later that year, she visited Man Ray in Paris and photographed him and his studio. This visit sparked her interest in photographic experiments - which she had done in the 1920s in the form of multi-exposures - once more. Inspired by his creative darkroom techniques, she created several multi-exposures.

(Her multi-exposure photographs are probably my most favourites works of all of hers…)

The Imogen Cunningham Trust

As Cunningham grew older, she became more concerned about the future placement and distribution of her work. Over the past seven decades she had accumulated thousands of platinum and silver prints and she also had around a hundred glass plates left from her early days in photography (those were the only remaining ones that she hadn’t destroyed when she moved from Seattle to San Francisco). She started inventoring them all and asked the Guggenheim Foundation for financial support to reprint all of her early negatives, which granted this enterprise.8

In 1975 she created The Imogen Cunningham Trust to manage and market her photography work, both during and after her lifetime.

Imogen Cunningham died on June 23, 1976.

Reading about the life of Imogen Cunningham, her accomplishments as a photographer and seeing the huge, diverse body of work she left behind impressed me. She decided to pursue a career in photography during a time when the societal role of women and their professional opportunities were very limited. And yet she went abroad to study and built herself a successful photography business in the following years. She did everything herself: from photographing to developing and printing in the Darkroom to everything that is needed to run a business.

Later she managed to balance her career as a successful business-woman and her responsibilities as a mother and proved that women must not choose between family life and a professional career.

Given the social norms of the time, Cunningham's decision to divorce her husband in 1934 was courageous and shows her strength and independence as a woman.

Her artistic contributions to the world of photography have brought her numerous awards, worldwide exhibitions, a reputation and many honours during her lifetime. She was a well-respected photographer and made important connections wherever she went.

She was a successful portrait photographer, but that didn't stop her from explore other fields of photography. She didn't limit herself to one genre but instead explored everything from still-life to street photography, architecture and multi-exposures.

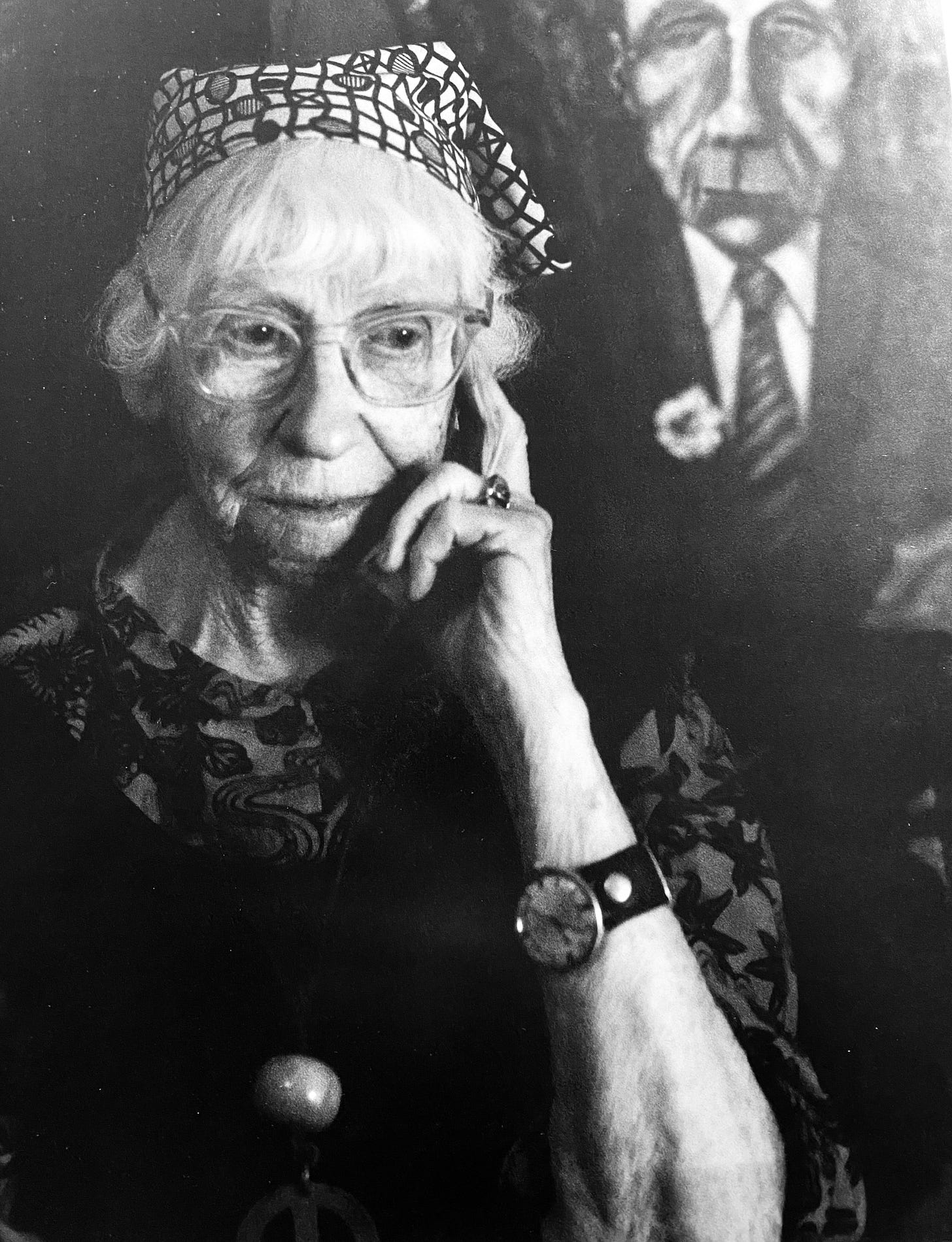

Cunningham kept photographing throughout her life. Even at the age of ninety-two, she started to work on a new project: photographing people of age. She called the project After Ninety, but never got to finish it.

“Photography is as wonderful to me today as it would be if I had never before seen a photograph. Let’s keep it so.

-Imogen Cunningham

Photography, it seems, was her life. And looking at her work, it must have been a good life.

If you want to learn more about her, I can recommend this short documentary about her, where she talks about her life and experiences as a photographer:

That’s it from me today.

Thank you for being here and for reading this week’s newsletter. It means a lot to me!

X,

Susanne

If you enjoyed this weeks topic, I would love to hear from you. Please share your thoughts in the comments with me.

If you enjoy My Morning Muse, you can support me by subscribing to my newsletter, liking the post, and sharing it with friends. It would mean the world to me! ❤️

Thanks to EubieCal for the great comment!

Richard Lorenz, “Imogen Cunningham. Pioneer of the 20th Century Photography” in Imogen Cunningham 1883-1976 (2001), Page 16.

Imogen Cunningham, “Photography as a Profession for Women” - The Arrow, Vol. 29, No.2 (Jan. 1913)

Richard Lorenz, Page 15.

https://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/cunningham/explore.html.

Richard Lorenz, P. 26.

Richard Lorenz, P. 20.

Richard Lorenz, Page 30.

Excellent. I just went to a Dorothea Lange exhibit yesterday at the National Gallery of Art in DC and wanted to look at more her contemporaries. Cunningham was one on my list, so this is a great start.

Incredible photographer and a wonderful essay on her life.

It’s so cool to see how these amazing artists all hung out and worked together