“Photography for me is a way of avoiding grown-ups, boredom and going to the laundromat. It allows me to live in another world, intensified and of my own finding. I assume the right to stare long and hard, to be blunt, loving and unselfconscious. I attempt to find a kind of poetry that eludes me in other more sober activities. It has become a continuous search with no shining end in sight except to go on trying.”

- Lilo Raymond1

One of the first photographers I featured in my little series of women photographers was Imogen Cunningham. After reading that newsletter, one of my readers got in contact with me and we chatted about photography. During our conversation, he suggested a photographer whose work I might also enjoy: Lilo Raymond. I hadn't heard of her before, but was eager to learn more.

A quick online search turned up a few of Raymond’s photographs, and I was immediately intrigued and decided to add her to my list of photographers to write about.

However, when I began my research for this newsletter, I realized there wasn’t much information about her. There’s no portrait of her available, no website featuring her work, and even her Wikipedia entry is just two sentences long. Something I find very odd considering the fact that her work is in the collections of museums like the Museum of Modern Art, the Getty Museum, and the Victoria and Albert Museum.

This is what I learned about her:

Lilo Raymond was born in 1922 in Frankfurt, Germany. At 16, she fled Nazi Germany and came to New York. Raymond began taking classes at the Photo League, a cooperative of photographers and filmmakers like Paul Strand, Ruth Orkin, Lisette Model, Aaron Siskind, amongst many others. However, she felt out of place there:

“I went to Sid Grossman’s class at the Photo League. I came to a class with some pictures I had taken, and I put them on pink and blue mattes, and everybody laughed. And that was it — I never picked up a camera again until my late thirties.”2

When Raymond returned to photography, she started studying under the legendary photographer and darkroom master David Vestal. It was during that time, she also began working as a commercial photographer, photographing interiors for magazines, and started exhibiting her personal work at various galleries. In 1977 she had her first solo exhibition.3

In the 1980s, Raymond moved to the Hudson Valley, where she continued her photography and began teaching at the School of Visual Arts and the International Center of Photography.4

She had a big retrospective at the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Modern Art in New Paltz, NY in 2008.

Lilo Raymond passed away in 2009 at the age of 87.

I couldn’t find any information about whether she was married or had any children. From what I could gather, it seems she dedicated her life and career solely to photography and teaching.

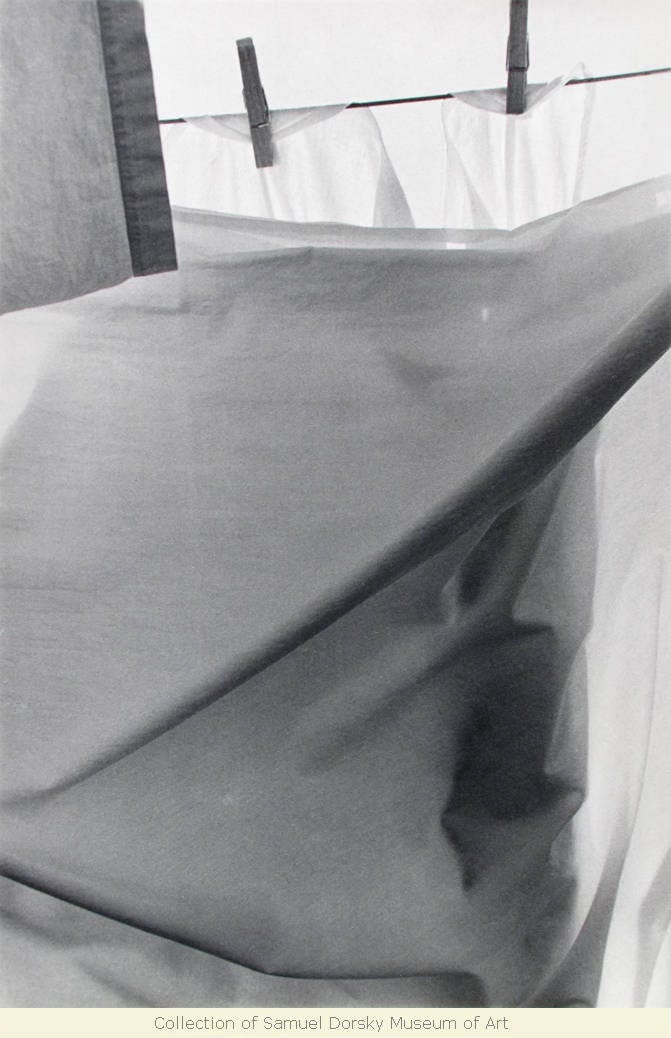

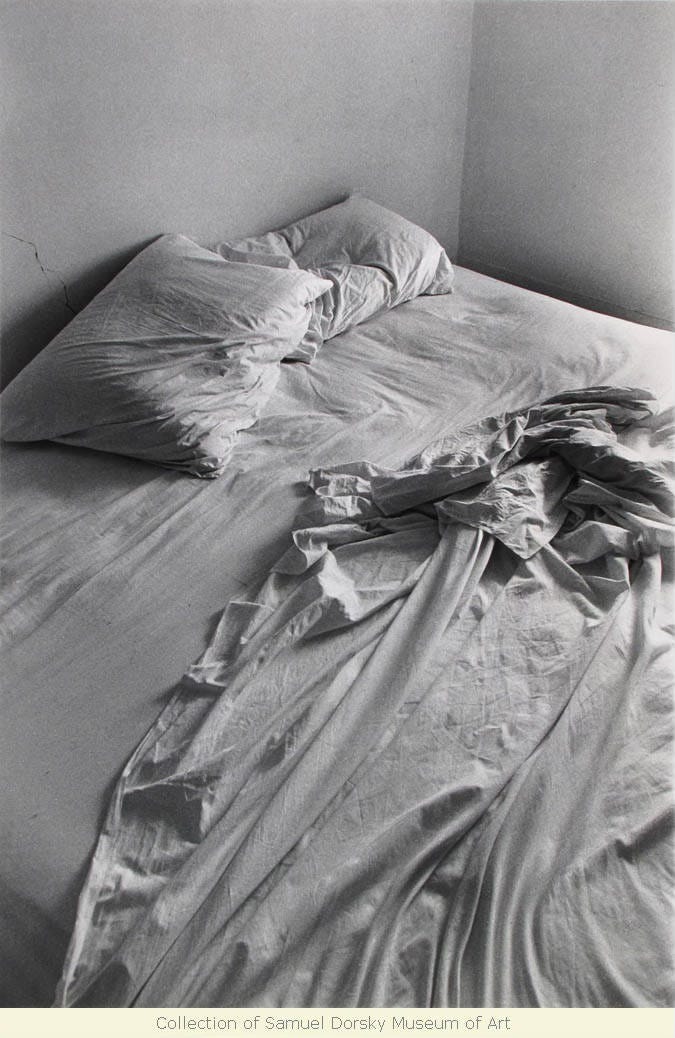

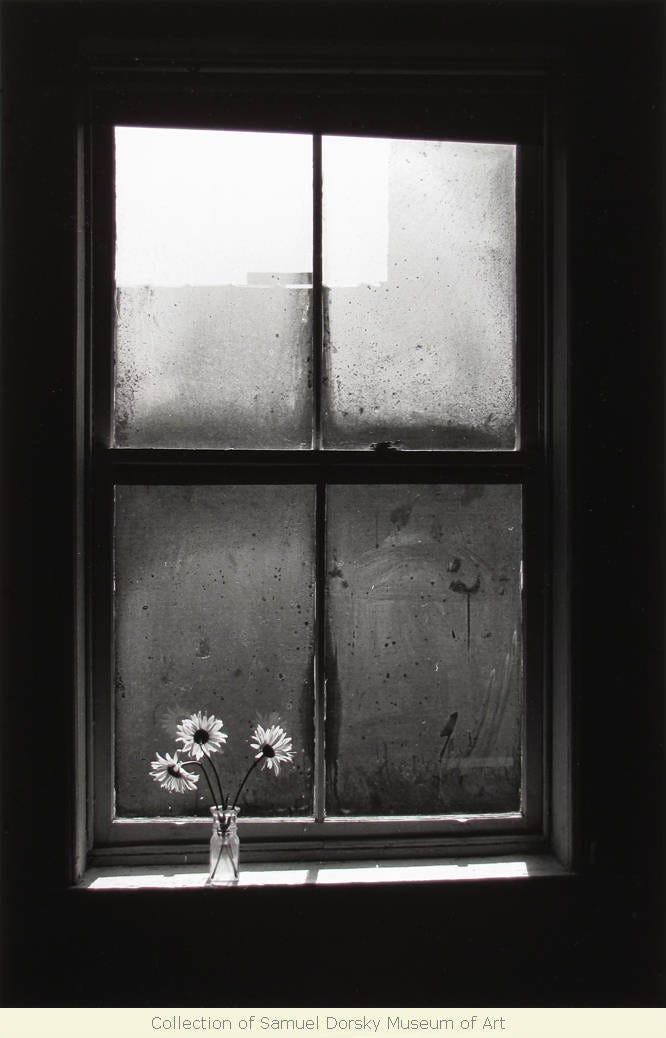

What drew me into Raymond’s work was her masterful use of light and space. Many of her photographs — primarily still lifes — depict quiet, domestic spaces that show traces of human presence without showing any people: an unmade bed, an empty plate on a table, a solitary chair. She transforms these mundane, everyday objects into visual poetry, imbuing them with an almost spiritual quality. The atmosphere in Raymond’s photographs invites the viewer to linger and enjoy these quiet moments she captured so well in her photographs.

The gallery “Photography West” describes Raymond’s work with the following words:

“In fact, it is possible to view Lilo Raymond’s photographs as manifesting a spiritual substitute for our culture of accumulation. By filling space, we diminish it; by letting it be, we support a condition in which we can be free. Lilo Raymond chides our shortsightedness. Her airy rooms suggest that beauty can lead an effortless existence and that a transcending elegance can flourish within the mortal precincts of the home.”5

Writing about Raymond and trying to learn more about her life coincided with a newsletter by Kenneth Nelson, in which he explored the question: What happens to our photographic legacy when we die?6 It’s an intriguing question. One I hadn’t considered before. With his words lingering in my mind, I found myself wondering about Raymond’s legacy. What became of it? From what I could gather, there seems to be no foundation dedicated to preserving her work — or if there is, it doesn’t have an online presence. As mentioned before: there are a few museums and galleries that hold some of her photographs, with the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art appearing to house the biggest collection of her work.7

That’s all from me this week.

Thank you so much for being here and for taking the time to read this week’s newsletter. It means a lot to me!

X,

Susanne

PS: I always love reading the comments, your feedback, and stories you share with me. It always makes my day. Thank you!

Writing these articles for My Morning Muse is both fun and rewarding, but it’s also a lot of work.

If you enjoy reading my weekly newsletter, please consider becoming a paying subscriber. For just €5 per month, your support helps me continue creating these articles.

Thank you so much for your support - it truly means the world to me! ❤️

https://photoquotes.com/quote/photography-for-me-is-a-way-of-avoiding-grown-ups-

https://www.chronogram.com/arts/portfolio-lilo-raymond-2173089

https://emuseum.hydecollection.org/people/1126/lilo-raymond;jsessionid=C7800BFE73861186E96B0F3683E9B6AF

https://www.chronogram.com/arts/portfolio-lilo-raymond-2173089

https://photographywest.com/artists/lilo-raymond/

Here is the article: https://substack.com/home/post/p-144056276

https://collections.hvvacc.org/digital/search/searchterm/Lilo%20Raymond/page/3

I really enjoyed this Susanne. I hadn't come across Lilo Raymond before - her work is very simple but very beautiful. Thank you for bringing her to my attention.

What beautiful photographs! Thank you Susanne for introducing us to yet another amazing photographer