Today’s newsletter is rather long and may be truncated in an email. You can click on "View entire message" to view the entire post in your email app.

Does a photograph or body of work have a deeper impact on you when you know the photographer’s story or learn more about their life and personality? Does that knowledge change or influence the way you feel about the work? Or does it help you to understand it better, or see it in different or new ways?

I often think about these questions, and usually, the answer to all of them is yes, especially in the case of French photographer Claude Batho.

A few months ago, I learned about Claude Batho while reading “What they saw - Historical Photobooks by Women (1843-1999)” by Russet Ledermann and Olga Yatskevich. The authors had one page dedicated to Batho’s book “le moment des choses…” which was published in 1977. There was a photo of a double-page spread from the book, showing two photographs of kitchen still lifes that caught my attention. I read the brief introduction about her book, career, and life, and then went online to see if I could find more information or more of her work, and maybe even a used copy of that book.

Because of her rather short career and life - she died of cancer at the age of forty-six in 1981 - there isn’t much to find on the internet. However, I found several more photographs she had taken and was mesmerized by them. Although I couldn’t find the book mentioned earlier, I did discover a monograph (see video above) published fairly recently, in 2023.

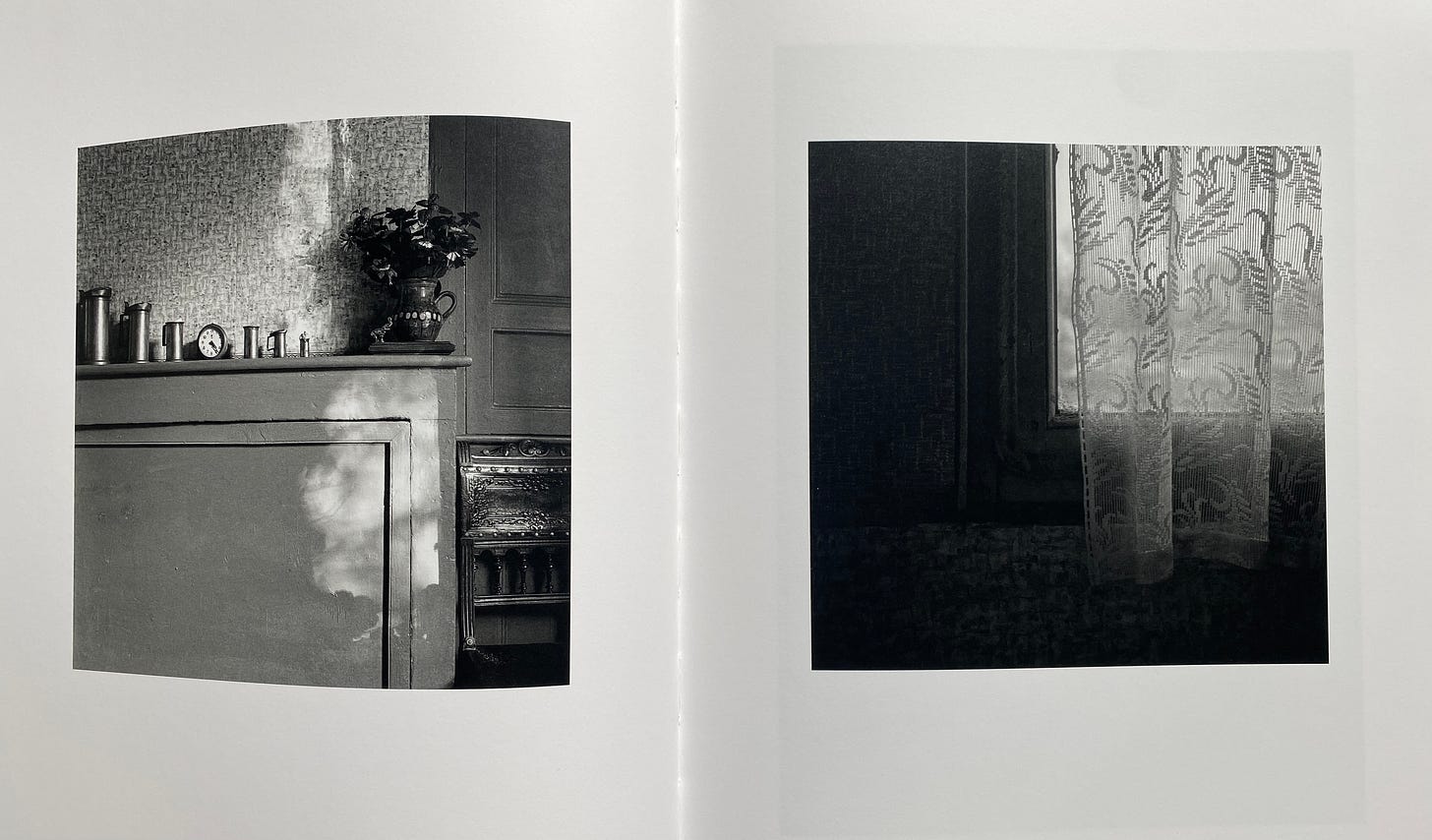

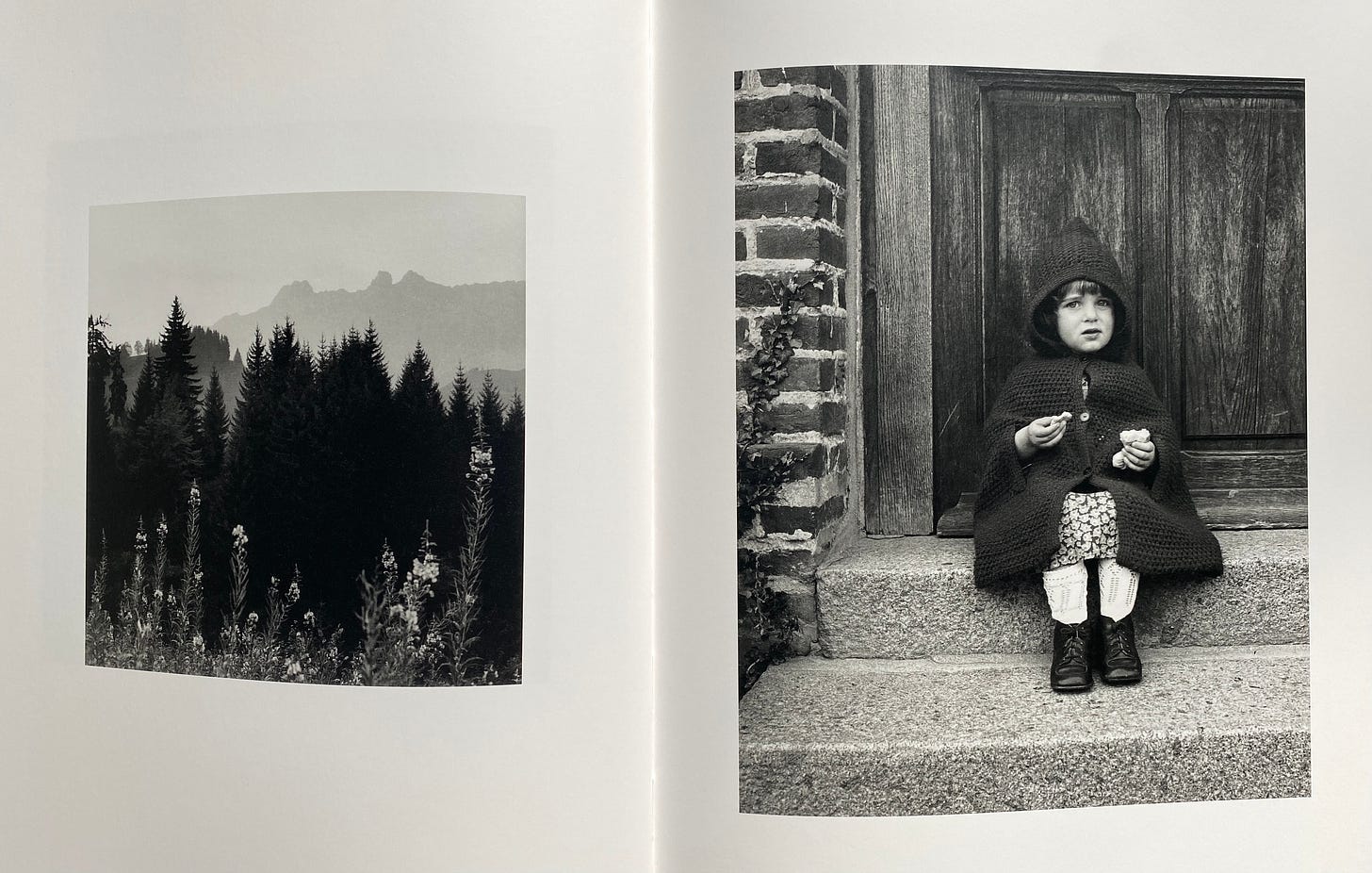

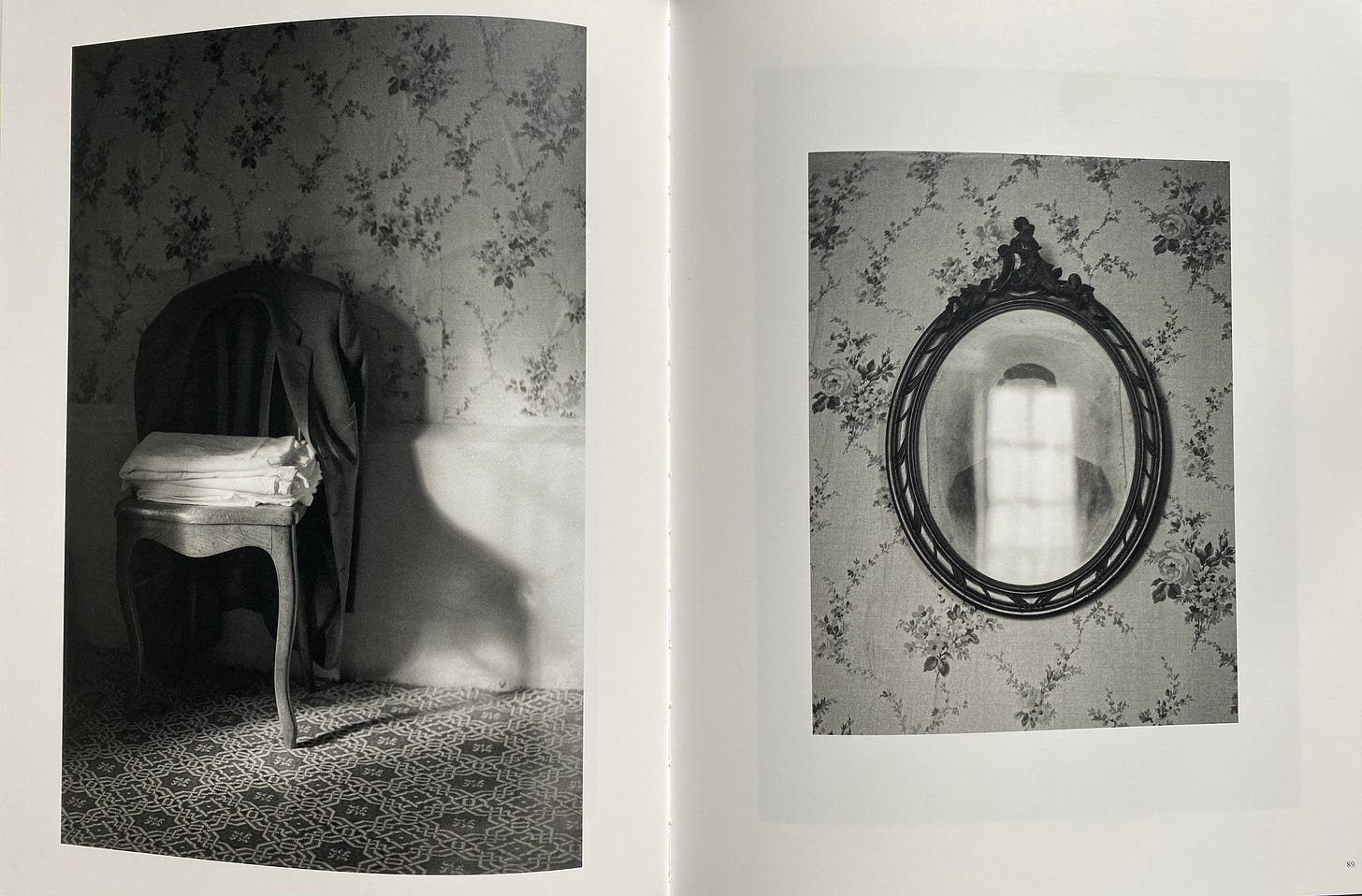

I ordered the book, and when it arrived, I quietly sat down with it and began to flip through its pages. It is such a beautiful book: the pages are made of heavy matte paper with a very slight sheen. The photographs are a mixture of moody landscapes taken somewhere in the French Alps, intimate family portraits, and fleeting moments of domestic life.

The photographs, which are arranged fairly chronologically, dating from 1956 to 1981, are beautifully sequenced and paired, which only deepened my experience looking at these photographs.

Here are a few of my favorite pairings in the book:

As I sat there with the book in my lap, closely looking at the images, I noticed that I reacted heavily to these images: I had a lump in my throat, my heart grew heavy, and feelings of nostalgia and melancholy overcame me.

After looking through all 180 pages twice, I took a deep breath and tried to understand what was going on. Why did these photographs have such a deep impact on me? Reflecting on this helped me to understand my feelings a bit better.

I was in awe of Batho’s talent. Her ability to see and make photographs of daily scenes in her home and of her family life was simply stunning. The light, the compositions, and her eye for small details are awe-inspiring. The intimacy and mood in her photographs are deeply moving. The scenes, which are mostly still lifes, don’t feel staged (although some of them probably were), but thoughtfully observed and composed.

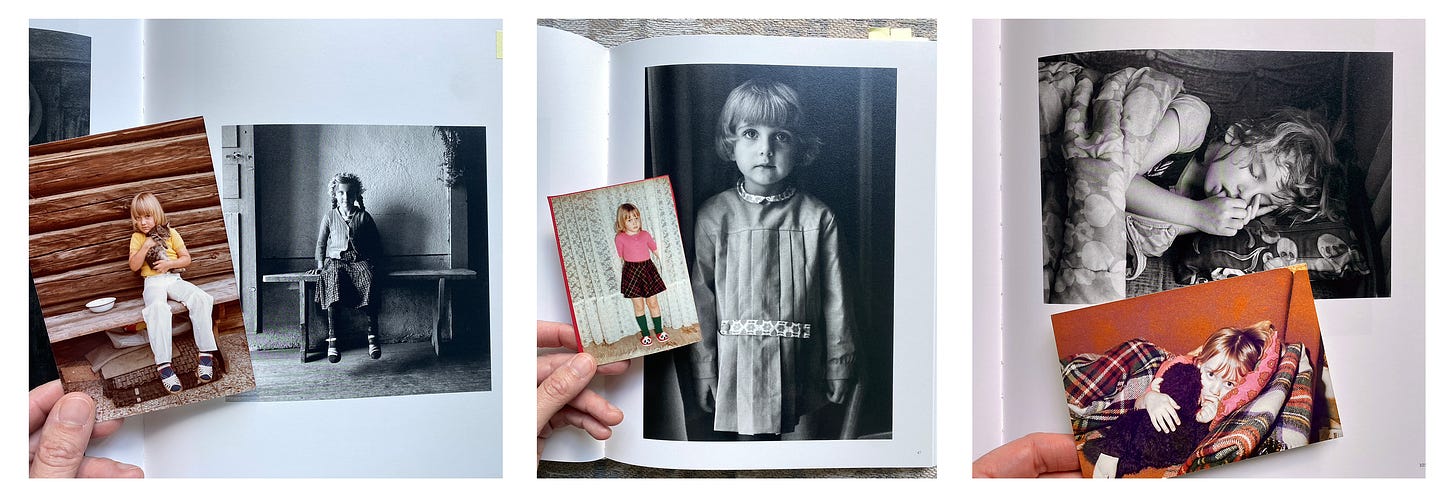

There is a familiarity in Batho’s images that touched me deeply. Some of the photographs transported me right back to my own childhood. Memories of moments long past, were flashing before my inner eye: summer breaks spent every year with the family on a farm in the Austrian Alps, me snuggling with my favorite stuffed animal on the sofa, me posing all dressed up in front of the window, the same dried flowers in a vase on the TV.

Three photographs of Batho’s daughters reminded me of photographs my parents had made of me. Not shown for artistic comparison, but how they triggered my memories. There were also many photographs of Batho’s that brought back more recent memories, as they reminded me of the abandoned places I had visited in the past few years, and of similar photographs I had made there.

But the most intense feelings probably came from my knowledge about Batho’s life:

Batho was introduced to photography by her father, who gave her her first camera. In 1950, at the age of 15, she enrolled in the École supérieure des arts appliqués Duperré in Paris. After graduating, she took a job at the documentary reproduction department at the French National Archives. This is where she met John Batho1, also a photographer, whom she later married and had two daughters with.2

With support from her husband, she worked on a series of portraits of their daughters, which was published as a book called “Portraits d’enfants” (“Portraits of Children”) in 1975. That same year, she was offered a solo exhibition at the gallery Agathe Gaillard, which was one of the first places in Paris that exclusively featured photography.

Two years later, another book, “le moment des choses” (“The Moment of Things”), featuring Batho’s photographs of the everyday of her private domestic life, was released by Édition de femmes, a feminist publishing house at that time.3

In 1979, at a time when photographic critique was still a rare genre in major daily newspapers, Batho had her work featured in the magazine Des femmes en mouvements, and also received favourable reviews in magazines like Le Monde and Le Figaro.

This period of suddenly acquired fame, paired with Batho’s cancer diagnoses, pushed her into her most intense and creative phase of her artistic life.

She died in 1981 at the age of forty-six.

Knowing about Batho’s tragically short life (and career) deeply influenced the way I looked at her photographs, especially the ones of her young daughters. One of them was born in 1973, just one year before me. I couldn’t find any information on the second daughter, but she was likely not much older. Looking at the photographs of these girls, imagining how young they were when they lost their mother, imagining that this could have been me, made my heart grow heavy.

I also found myself in Batho’s shoes, knowing she died around the age I am now. It was difficult for me to fathom what she must have been going through, battling cancer, and facing the prospect of leaving behind a husband and two young daughters.

What stands out to me is how much Batho’s photography changed in her final years. Although she continued to photograph the same subjects, the way she saw and photographed them felt different. It seemed as if she poured much more of her inner world into her work. Her images became darker and more introspective.

For example, many of her photographs from that time were taken through fogged or misted windows. What lies beyond is barely visible, which to me feels like a metaphor for the uncertainty of what was coming next. Also, the way she photographed her children changed - they rarely look at the camera anymore. Instead, they appear hidden behind curtains or are shown from behind, creating a sense of distance.

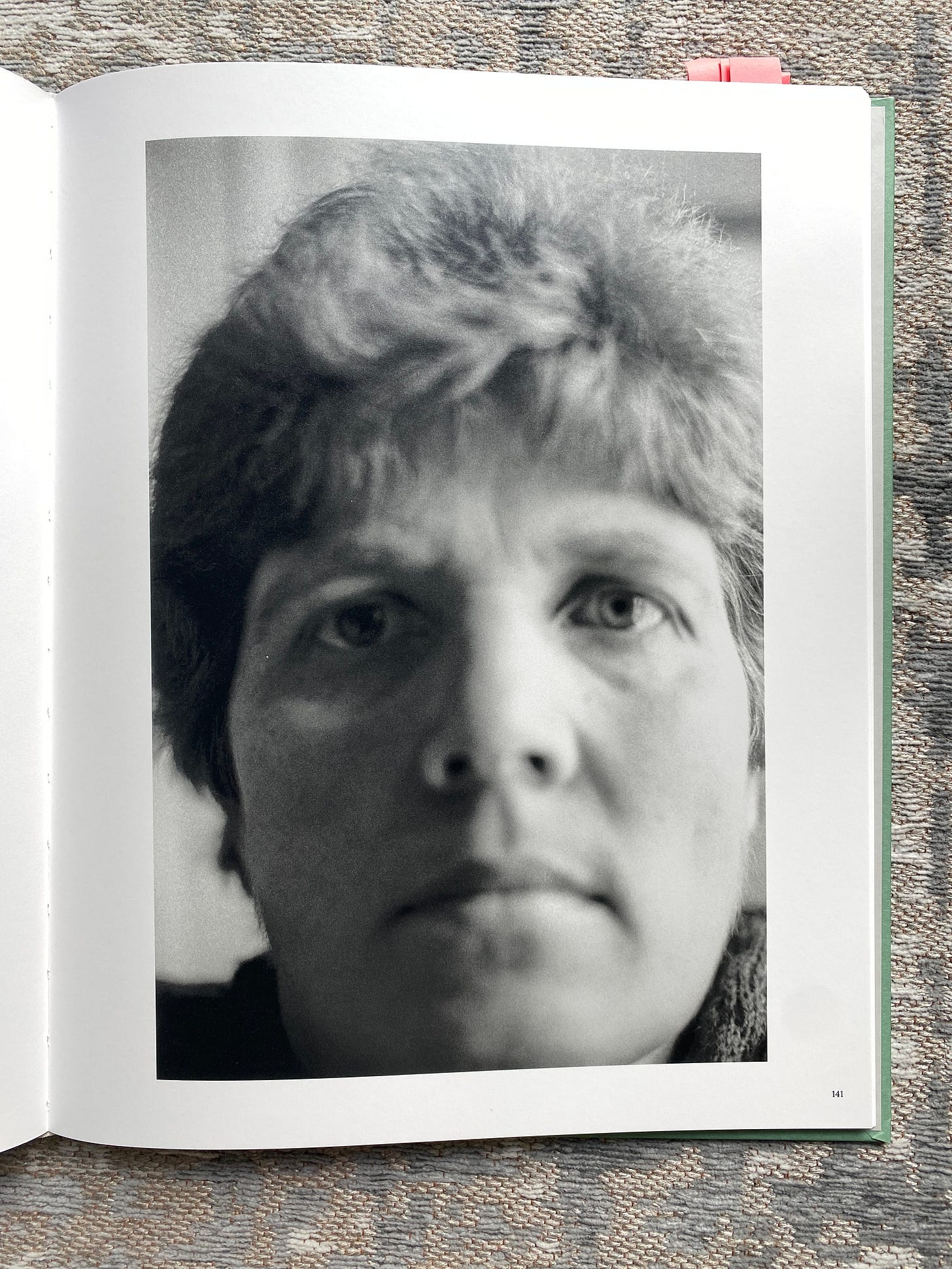

In the first 140 pages of the book, Claude Batho seems to consciously avoid appearing in her own photographs. There are many images of furniture with reflective surfaces—mirrors, glass doors—but never does her reflection appear. You can often see what’s on the other side of the room, yet Batho herself is always absent. It happens so consistently that it stood out to me.

Then, on page 141, a photo taken in 1980 - one year before her death is shown:

One hundred and forty pages—without a single glimpse of her—and then suddenly, she’s right there, face to face with the viewer. As if to say, “I’m here. Don’t forget about me.” And yet, the image is blurry, as if she’s already beginning to disappear from the world.

Near the end of the book, there are also a few double exposures from 1980 - two images layered over one another, as if she were already inhabiting two different worlds.

In the foreword of the book, Coline Olsina mentions that Claude Batho never saw the last photographs she made. Her husband, John Batho, found the last five rolls in her drawer and developed them himself.4

This is how we know this was the last photograph before her death:

“J'ai voulu rendre sensibles des instants très simples, en retenir les silences.”

"I wanted to make simple moments felt, to hold onto their silences."

- Claude Batho

I began my mission to write about female photographers after standing in front of my bookshelf one day, realising how much my photobook collection was dominated by male photographers.

I am a self-taught photographer with no formal art history or photography education. I do not have the expertise or knowledge to give you a deep analysis of the work, nor do I see myself as intellectually equipped enough to place the work within a historical context.

My aim is simply to share the work of women photographers who inspire my creative journey – along with their stories and unique perspectives on the world they live(d) in.

If you are interested in reading more, you can find all past editions here.

That’s all from me this week.

Thank you so much for being here and for taking the time to read this week’s newsletter. It means a lot to me! Feel free to leave a comment – I always love to hear your thoughts.

X,

Susanne

WAYS TO SUPPORT MY MORNING MUSE

If you enjoy reading my weekly newsletter and would like to support my work, here are a few ways to help me keep going:

🪶 Like, share, or comment - it’s free and greatly appreciated

🪶 Upgrade to a paid subscription (only €5 per month)

🪶 Purchase one of my zines

🪶 Treat me to a cup of tea

Thank you so much!

https://www.john-batho.com

https://awarewomenartists.com/en/artiste/claude-batho/

Russet Ledermann / Olga Yatskevich: “What they saw - Historical Photobooks by Women” (2021), page 237.

Coline Olsina: “Claude Batho: “instants trés simples” (2023), Page 15.

This is such a well written article on Claude, Susanne - you've described how her work and life story impacted on you so openly that I can almost sense the deep emotional connection you hold within this piece. Adding your childhood photos really emphasised this connection.

Her work is truly beautiful so thank you for introducing her - I'm off to join others in hunting for her book!

Thank you for sharing. The images are quietly powerful and all the more so knowing her backstory. Well told and shown…