“Inevitably, my work has an autobiographical element: it’s connected to my childhood, to my dreams, to my spirit, to what I feel in the moment I take a photograph. I’m probably somewhat selfish, in as much as the photographs I take are for myself. Yet, everything I’ve done, everything I’ve seen, has allowed me to understand the world better, in this moment in which I’m living.1

Graciela Iturbide didn’t want to be a photographer. From a young age, she wanted to become a writer or study philosophy, but her conservative parents did not support her dreams.2

It was only later in life - she was already married and had three children - that she decided to study cinematography. Her husband supported her idea and in 1969 - at the age of 27 - she enrolled at the film school at the Universidad Nacional Autónama de Méxicoto.

She began to take photography classes with Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Latin America’s most prominent modernist photographer of the time and became his assistant. In the following two years, they would travel around Mexico, visiting villages and popular festivals. Iturbide would observe Bravo while he patiently looked for the right place and waited for the right moment to photograph anything of interest to him.

This apprentice with Bravo - Iturbide would later say - was a life-altering experience. It was because of him that she wanted to be a photographer.

“He instilled in me a poetic sense of time and timelessness, so Mexican in nature, that was also his own.”3

Besides teaching her the technical aspects of photography, he also opened her eyes to a whole new world filled with poetry about the cultural heritage of her native land which she hadn’t really felt connected to before.

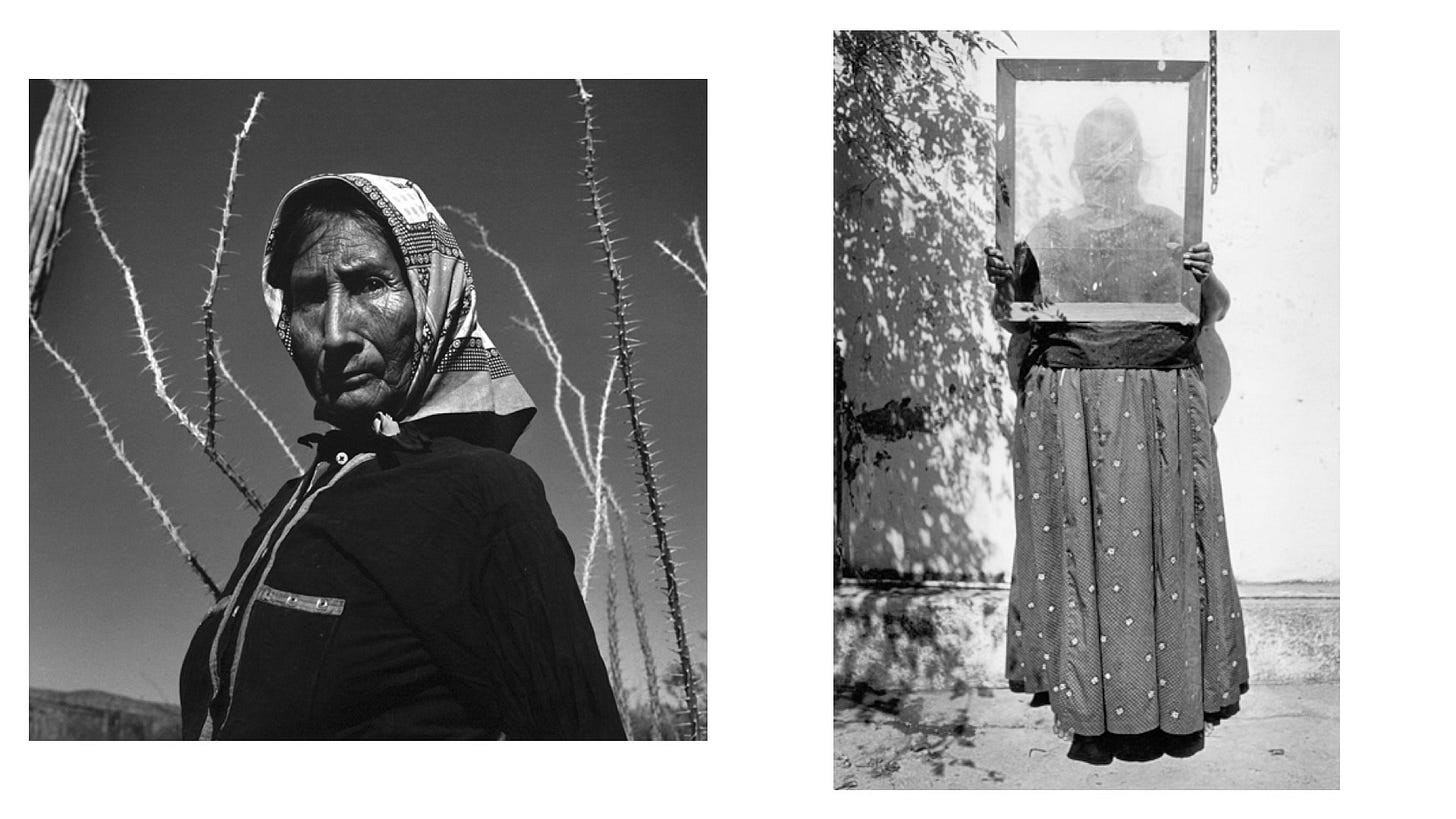

In the following two decades, Iturbide would create her most iconic work. The first big commission she received in 1978 when the Ethnographic Archive of the National Indigenous Institute of Mexico asked her to photograph the Seri, an Indigenous group that lives in the Sonoran Desert of northwestern Mexico.

In 1979, she was invited to photograph the Juchitán people who are part of the Zapotec Culture native to the Oaxaca region in southern Mexico.

Iturbide’s approach to photographing these communities was straight-forward, yet empathic and respectful. It was important to her, that she wasn’t just seen as the outsider with the camera, but to become a part of the group. She never forced anyone into being photographed, and never took photos when she felt it wasn’t appropriate. This way, she was able to gain their trust, to work and live with them and to become their cómplice as Iturbide calls it.

“I never take photos in secret and I’ve never used a telephoto lens. My subjects always know I’m there as a photographer and, if I feel someone doesn’t want their picture taken, then I don’t take it.”4

Between the 1970s and 1990s Iturbide’s subjects ranged from indigenous groups and children’s funerals to transgender communities, and gangs like the Mexican American White Fence Gang in Los Angeles. Her photographic journeys would bring her to India, Japan, Italy, Spain and many other countries where she would photograph the places and its people.

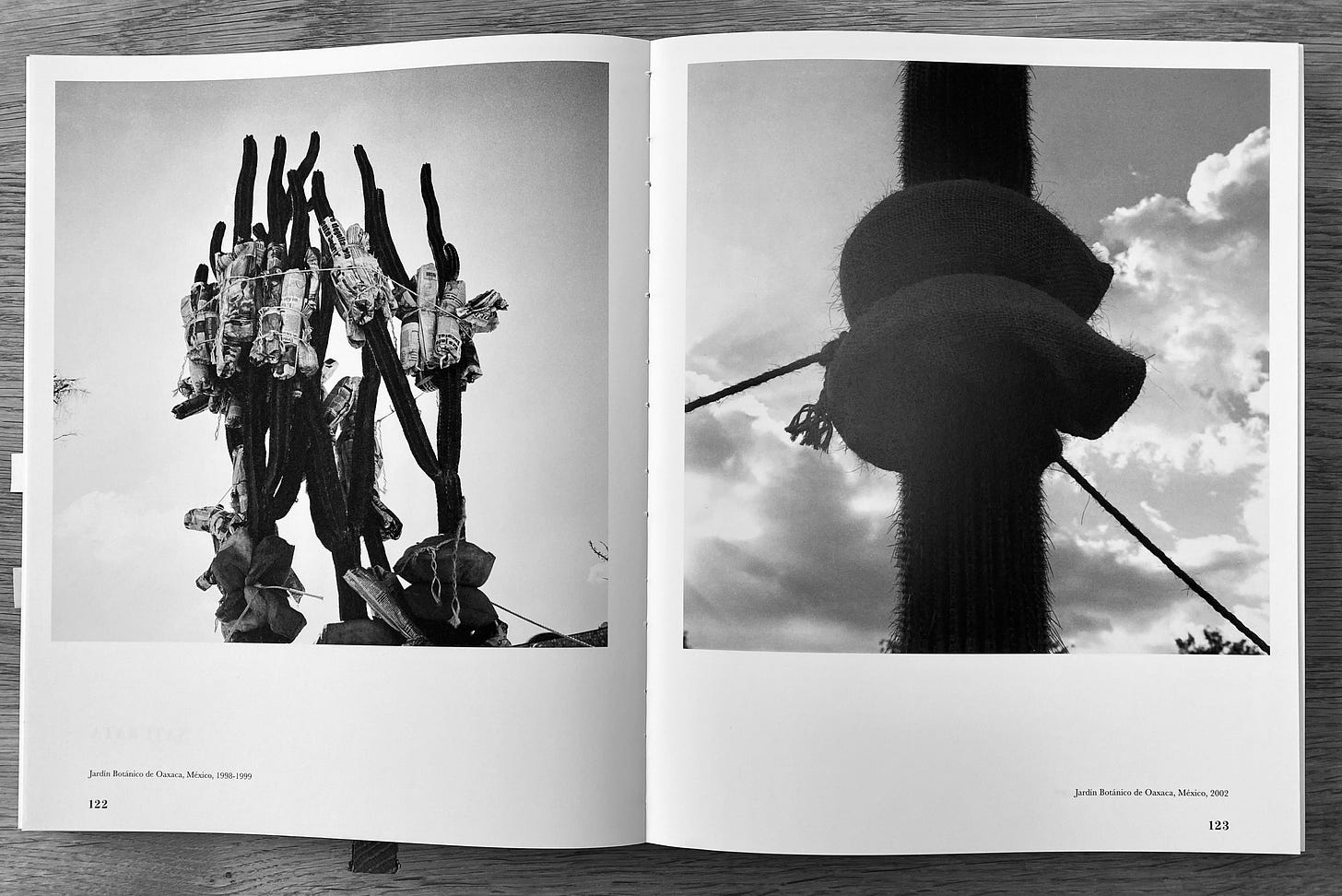

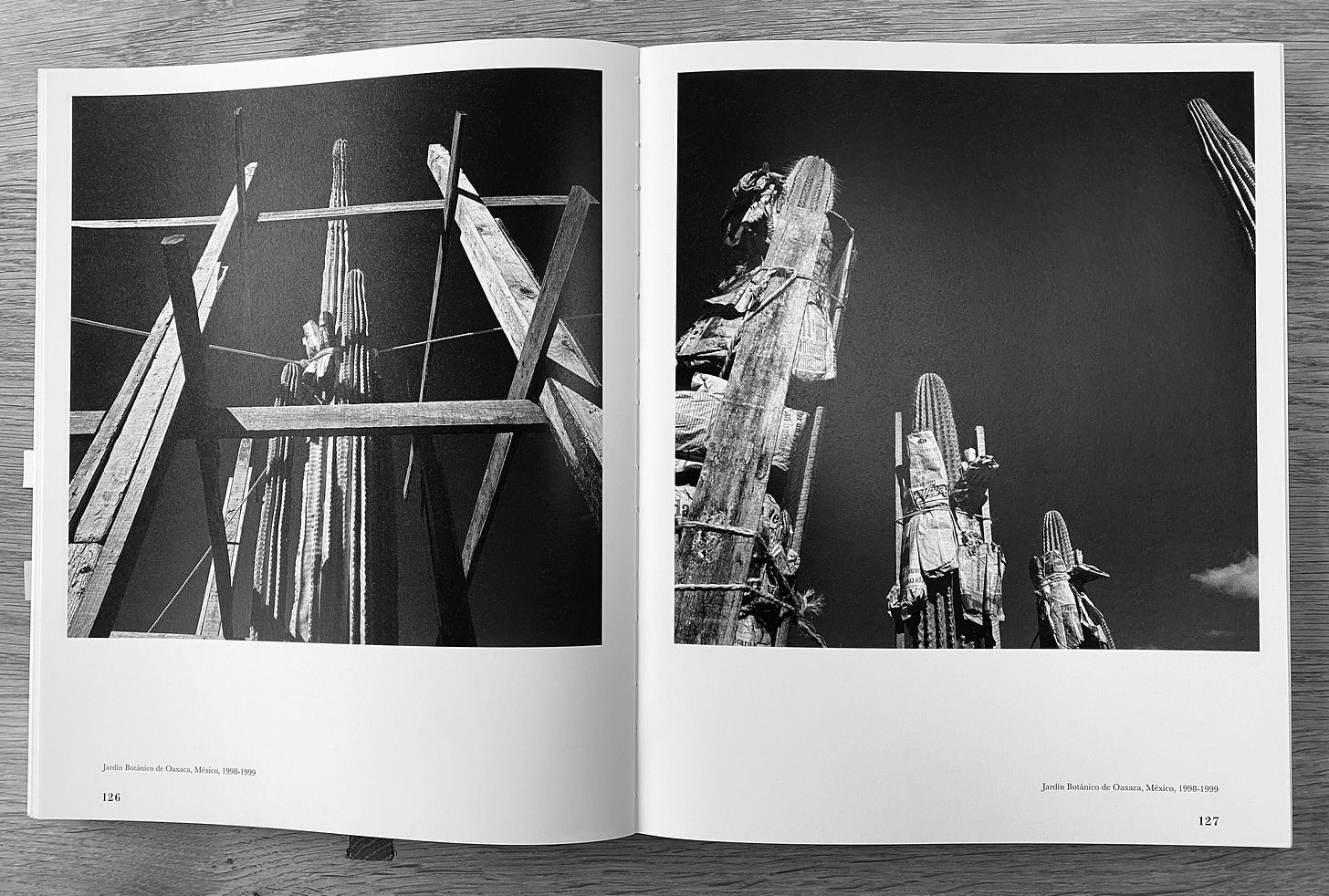

Over the years though, her focus shifted away from people and she became more interested in the landscape as a subject for her poetic imagery:

“My images have become more silent and reflective with time. My gaze has shifted to the open sky, to landscape, to nature. In recent years, I have felt myself drawn to what’s elemental: rocks, water, air, clouds, dust. My quest for primal forces is just beginning, and I don’t know where it will lead.”5

The first project in which Iturbide turned her attention away from people and towards nature and abstract photography is called Naturata. Between 1996 and 2004, she photographed the botanical garden of Oaxaca, Mexico which was under restoration at that time. All the plants and cacti were covered in nettings, held in place by ropes, wrapped in burlap sacks or supported by iron shafts. For Iturbide, all these plants had a strong sculptural character.6 And her stunning photos make clear why:

But no matter where in the world Iturbide would travel to, who or what she would photograph, the aspects of culture and identity are always entailed in her work. Not only the culture and identity of the places she visits but also her own.

“Photographs emerge from both exterior realties and our inner selves - from within and without.They cross paths, but we also carry them. This is why I believe that photography is largely a matter of self-discovery. When I look at the images I have made, I see not only the fragments of the world I have been able to capture, often by chance, but also observe the imprint of my interpretation, projections, desires and dreams.”7

Iturbide sees herself as an explorer and says that many of her photographs are the result of unexpected encounters and unforeseen occurrences. She calls intuition, chance and wonder fundamental components of her photography. When photographing, Iturbide is always following her eyes and her heart. The moment of surprise or wonder is the moment in which she will press the shutter.

According to Iturbide, this spark can be found anywhere: in people, buildings, landscapes, things; in rituals and everyday life; in any action or event. Because everything for her is connected.8

Graciela Iturbide is best known for her early black-and-white photographs of the Mexican people and culture. Her striking portraits of the women of Juchitán were what first drew me into her work. Discovering her abstract colour work was exciting and interesting for me because all the work she had created before was exclusively in black and white.

I love Iturbides work for its visual qualities: it’s bold, and pure, has a lot of contrast and her sense of composition is amazing. What I value just as much are the poetic and mystic qualities her photographs contain. The borders between reality and surrealism are often blurred and leave plenty of room for the viewer to use their own imagination of what is going on in the photograph.

Reading her thoughts on photography resonated so much with me that it became the main reason I wanted to include her in my little series of female photographers. The way she uses photography and what it means to her is very much aligned with my own thoughts and the ways I use photography. Maybe that’s another reason why I am so intrigued by her work…

If you would like to dive deeper into her work and read more about her definition of photography and what it means to her, I can highly recommend the following two books:

“Graciela Iturbide on Dreams, Symbols and Imagination” - The Photography Workshop Series published by Aperture (2022).

This book features a lot of her older works, but a few newer ones too. It contains her writing which makes it very interesting. You learn a lot about her ideas behind her photographs and how she uses photography to express and explore herself.

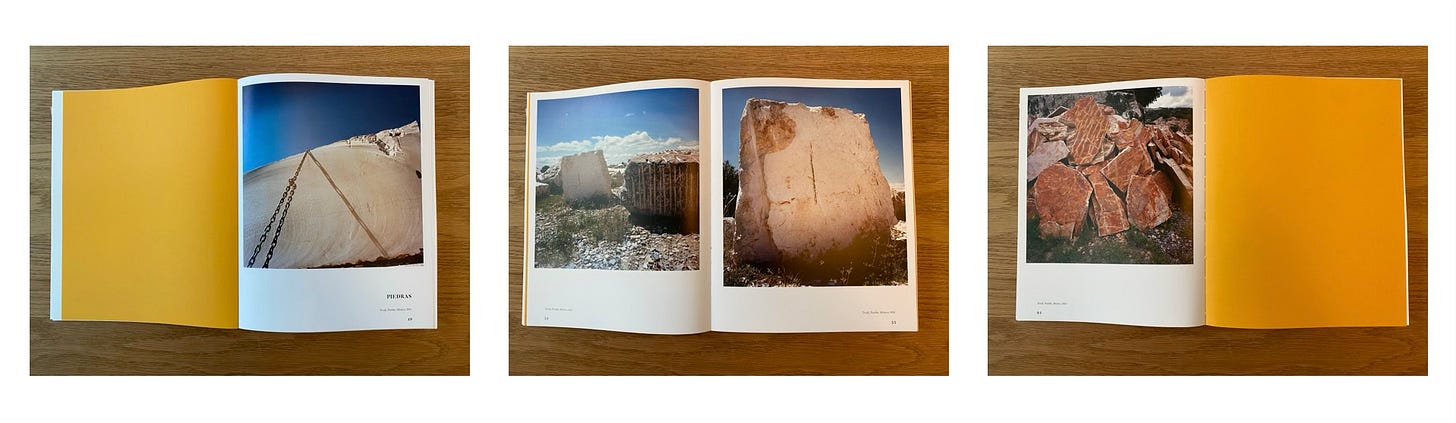

Graciela Iturbide in “Graciela Iturbide: Heliotropo 37”. Published by The Fondation Cartier (2022).

This book was a big surprise because it features Iturbide’s colour photographs. A series she has worked on in recent years. It also contains a long interview, in which Iturbide talks about her career, her life and the meaning of photography. It was very similar to what she wrote in the Aperture book. The size of this book is twice the size of book #1, therefore the photos are bigger and it has much more pages. And it is beautifully made (if you care about this).

I can recommend both books, but you really just need one in my opinion. If your budget allows it, get the Heliotropo 37!

That’s it from me today.

Thank you for being here and for reading this week’s newsletter. It means a lot to me!

X,

Susanne

Were you familiar with her work? What do you think about her photographs or what she says about phootography? Please share your thoughts in the comments with me. I would love to hear from you!

Writing these articles for My Morning Muse is fun, but it takes hours of work.

If you enjoy reading my newsletter, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. With only $5 per month, your paid subscription helps me to keep going.

Thank you so much for your support. It means the world to me! ❤️

https://www.frieze.com/article/graciela-iturbide-democratic-nature-photography.

“Graciela Iturbide on Dreams, Symbols and Imagination” - The Photography Workshop Series published by Aperture (2022), Page 14.

See page 14.

https://www.frieze.com/article/graciela-iturbide-democratic-nature-photography

“Graciela Iturbide on Dreams, Symbols and Imagination” - The Photography Workshop Series published by Aperture (2022), Page 116.

Graciela Iturbide in “Graciela Iturbide: Heliotropo 37”. Published by The Fondation Cartier (2022), Page 42.

“Graciela Iturbide on Dreams, Symbols and Imagination” - The Photography Workshop Series published by Aperture (2022), Page 8.

See page 26.

i was not familiar with her work but now, thanks to you, i am. and i love it. her thoughts about photography are food for thoughts and i agree with shital: there's nothing selfish about taking photos for yourself. if taking photos is about self-discovery, how can this be selfish?

Susanne, I don’t think photographing for yourself is a selfish act at all! Interesting to read about Iturbide’s photography and her life.