It was on November, 10th 1956, when 19-year-old Pierre Cordier wanted to send a birthday card to his friend Erika in Germany. He took a piece of light-sensitive paper and wrote with nail varnish his dedication on the paper. Because he wanted a black background, he put the piece of paper into a chemical solutions (developer and fixer) in which one would usually develop its photographs. Soaking the paper in the developer made it turn black as planned, but another thing happened as well: the nail varnish reacted with the chemicals and slightly came off. Where the nail varnish had disappeared the white of the paper became visible. He dipped the paper into the fixer to keep the white border around his writing.

That’s when the chemigram was born. From then on, the Belgian artist dedicated his career - over-spanning five decades - to exploring and defining his newly discovered technique.

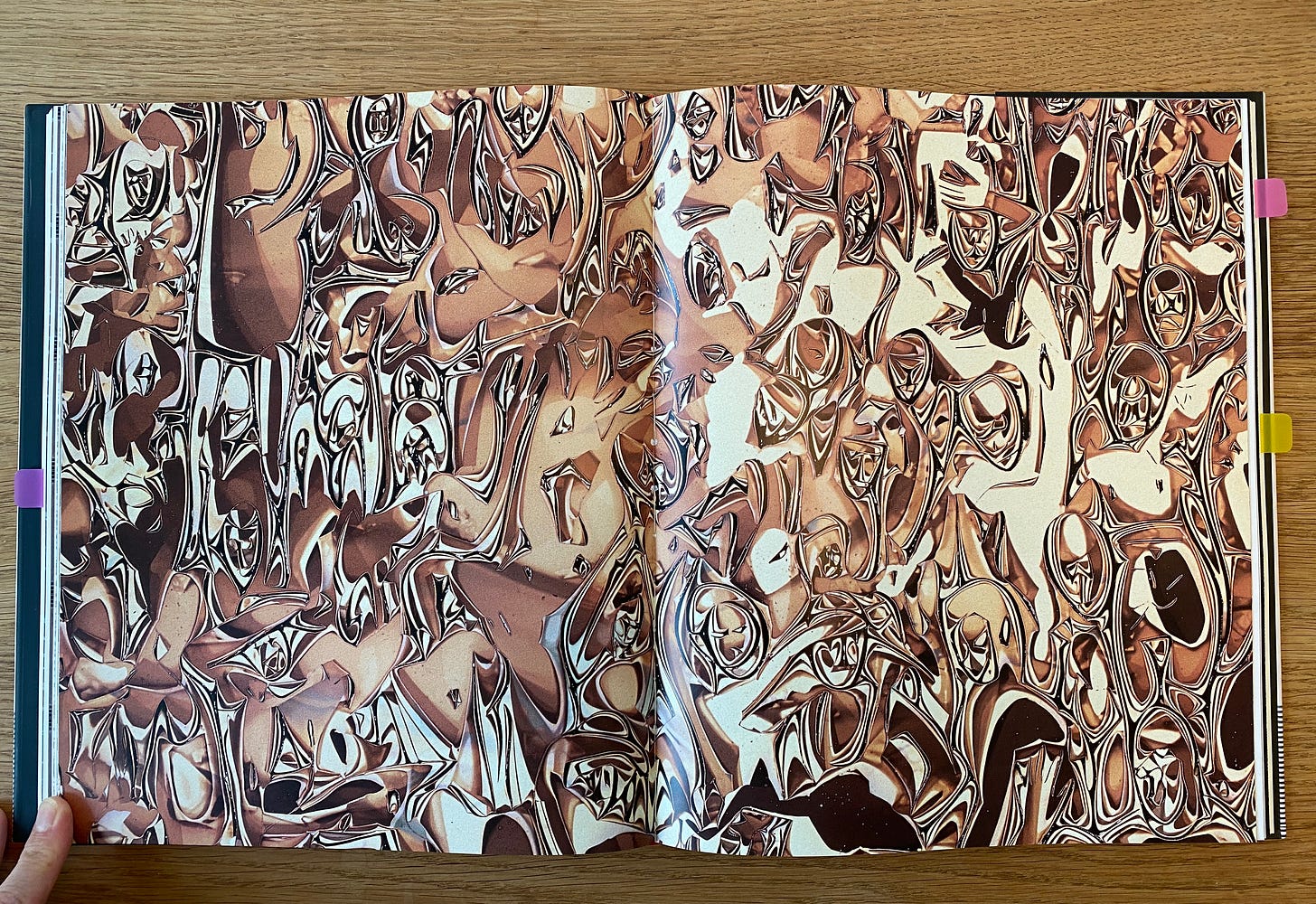

If you haven’t seen a chemigram before, it is really difficult to describe what it can look like. And even if you look at one - like the ones in this newsletter - you still can’t be sure what you are looking at or how it has been created. It doesn’t look like a photograph but also has little in common with a painting. Chemigrams challenge the typical classifications of art, because they are neither one (painting) nor the other (photography).

Cordier described his technique as a combination of

the physics of painting (varnish, wax, oil) with the chemistry of photography (light-sensitive emulsion, developer, fixer), without the use of camera, enlarger, and in broad daylight.1

But this only gives us an idea of the different materials Cordier used. It doesn’t really describe the magical, visual appearance of a chemigram. Pierre Sterckx uses the following words to describe Cordier’s work:

“Cordier’s chemigrams are mosaics whose incrustations question the relationship between logic and chance, form and substance, decorative motif and image. Never does a fragment of space appear as a form or an image in itself. The sparkling gems of the chemigram speak more about time than space.”2

When the photographer Brassaï discovered Cordier’s work, he wrote to him “how very diabolic and beautiful your process is. Make sure you never divulge it.”3 But Cordier enjoyed this process so much, he wanted other people to know about and learn it too, so even more people would enjoy it. He even teached it at the École nationale supérieure des Arts visuels de la Cambre in Brussels for many years.

In the book “Pierre Cordier: le chimigramme” Cordier goes into depth describing his different techniques using his chemigrams as examples. Reading these “instructions” helps to understand a little more how he achieved the different results, but it doesn’t take away the magic of his creations - as it does if a magician reveals the secret behind his trick. They still remain wonderfully puzzling and mysterious.

First, the patterns of some of the chemigrams give you the impression that this is something that has been created digitally - like a cryptic computer language - and not by dipping a piece of photo paper which is covered with nail varnish, olive oil or body lotion back and forth in photographic developer and fixer.

But if you look closer, you realize that the repetitions of the patterns are never the same and very unique in their appearance. More like something organic. Textures and patterns you would more likely find in nature: like the rings of a tree, the veins of a leaf, the rusty patterns on a decaying car door or bacteria in a petri dish viewed by looking through a microscope.

When I read about Cordier’s passing in March of this year, I remembered how much I enjoyed making chemigrams and how fascinating this technique is to me.4 My chemigrams are by far not as elaborate and complex as Cordier’s. They don’t come even close to his jaw-dropping and mind-boggling creations, but that wasn’t my goal when I created them. Making art, whether it’s collage, mixed media or photography, allows me to explore different themes and questions, often focusing on the passage of time and the transience of life. Making these chemigrams allowed me to approach those themes from a different angle.

I like the experimental side of making chemigrams and the element of chance which often brings surprising results. The creative possibilities of this technique are endless and so are the ways to read and the meanings you can give them.

The process can be as simple as: applying the resist5, making marks if desired, alternating the photo paper between the different trays of the chemical solutions, and watching how the patterns on the paper slowly appear on the paper while the resist slowly dissolves has something very calming and yet exciting to me. And even if you understand what is going to happen next, it always feels like doing a magic trick. I never get tired of creating them (or do they create themselves?), looking at them or come up with new associations, meanings and words I associate with them.

If you want to learn more about Pierre Cordier and his chemigrams you can check out his website.

I hope, I will be able to view his work in an exhibition one day because I believe this is the only way to experience Cordier’s work in all its capacities.

In the meantime, I will enjoy looking at them in a book I can highly recommend: “Pierre Cordier: le chimigramme”. It is a wonderful photo book filled with his creations, a few essays and a chapter in which Cordier describes his technique in depth.

That’s it from me today.

Thank you for being here and for reading this week’s newsletter. It means a lot to me!

X,

Susanne

Are you familiar with chemigrams? What do you think of them? How do they look like to you? I would love to know your thoughts about this technique.

https://museemagazine.com/culture/art-2/features/meet-the-photographer-pierre-cordier

“Pierre Cordier: Le Chimigramme“ Published by Éditions Racine, 2007, Page 31.

One of my newsletters here was about it. But because I experimented more with Chemigrams, I decided to make a new post.

www.youtu.be/GgAareEne3s?si=BZewr3VZUzpX-DQA

Which can be everything from oils, to paint, to products like shampoo or tooth paste.

This process is more on my bucket list. Thank you.

What a discovery, Susanne! Thank you for introducing me to Pierre’s work. I haven’t heard of Chemigrams until I read your post. Please continue to show your experiments as it seems to be a fun process!